Charlayne Hunter-Gault on Her New Book and 50 Years of Reporting on Black Life

This article is part of the series In Their Own Words, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

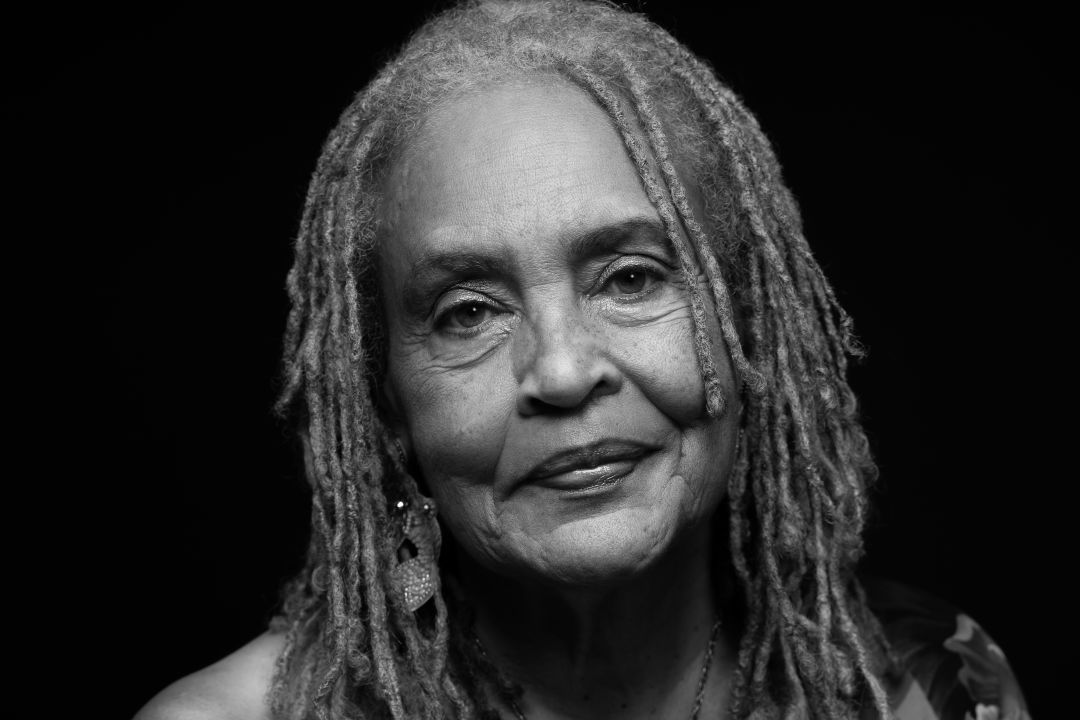

Charlayne Hunter-Gault

Image: Michael Kinsey

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, “We are not makers of history. We are made by history.”

However, with all due respect to King, Charlayne Hunter-Gault is both. Before she blazed a trail reporting about the lives of her fellow Black Americans, Hunter-Gault made history by becoming the first Black woman to integrate the University of Georgia (UGA) in 1961. Together, she and Hamilton Holmes—the first Black male to integrate UGA—took their first steps into the university while facing harassment, assault and a violent mob demanding their expulsion. They set fires outside Hunter-Gault's dormitory and hurled bricks and rocks through her window.

But Hunter-Gault didn't let that stop her. She rose to meet the moment with a career in journalism that shines a light on Black life, has spanned more than five decades, and includes two Emmy Awards and two Peabody Awards.

Hunter-Gault's writing has appeared in The New Yorker, where she was the first Black reporter for the magazine's "Talk of the Town" section, and The New York Times, where she founded the newspaper’s Harlem bureau in the early 1970s. In 1977, she became a PBS correspondent, hosting the award-winning South African NewsHour series “Apartheid’s People.” While in residence in South Africa, where she lived for more than a decade with her husband Ronald Gault—then-head of JP Morgan’s office in Johannesburg—she also covered African news as the bureau chief for both NPR and CNN.

Hunter-Gault has also published five books. Her latest, My People: Five Decades of Writing About Black Lives, was published last month, with a foreword by Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones. The book provides an encyclopedic record of the evolution of her work spotlighting Black life in America, from its struggles to its triumphs.

Today, at 80, Hunter-Gault continues to write and work; she and Ronald split their time between Sarasota and Martha’s Vineyard.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Tell us about your childhood.

“Although there was legal segregation, I had a very full childhood. The support I received from my community helped me feel like a full person. It’s said that it takes a village to raise a child and mine, on Brown Street in Covington, Georgia, where I grew up, was engaged in just that: helping parents bring up their children. Sometimes, while making lunch, my nice next door neighbor would offer food to me. On the other hand, if a child was misbehaving, an unspoken license for punishment existed between parents.

“While the Black community suffered the effects of discrimination of the separate and unequal laws of the time, everyone—from those at Washington Street School to the AME church—engaged in making us feel like whole people. Even though our schools were poorly staffed, equipped by white leaders with old, hand-me-down books from white schools with pages missing, it did not deter the teachers from raising our consciousness about who we were.”

How did you develop the fortitude to forge ahead against racism and discrimination?

“One instance that comes to mind is when I won a diamond tiara at my school’s annual fundraiser. My mother and grandmother had raised the most money by collecting nickels, dimes and a few dollars, which earned me that tiara and a Bulova watch. Now, my parents weren’t poor, so the watch wasn’t exciting, but I wore that tiara everywhere, except while sleeping. After my schoolmates teased me enough, I finally took it off, but the notion a being a queen stayed in my head.

“Our schools also, in an effort to create an armor around the children, taught us Black history. They were dedicated to it. It was so effective that when I was at UGA and the rioters were shouting the n-word, I looked around to see who they were talking to—I was sure that it wasn’t me. Even under those difficult circumstances, ugly taunts, and challenges, I knew that I had the strength and support of those around me, as well as those who came before me.”

What inspired you to become a journalist?

“My grandmother read three newspapers every day, and when she finished, she’d give me the funny papers, which is where I discovered "Brenda Starr, Reporter," a comic strip about a glamorous journalist who traveled the world. When I told my mother, who was strong, well-educated and understated, that I wanted to be like Brenda Starr when I grew up, she never discouraged me with the words that so many little Black girls heard—that we didn’t do things like that.

“Also, while attending Henry McNeal Turner High School, I learned about Ida B. Wells, the Black journalist who was as daring and successful in real life as was Brenda Starr in the comic strip. And there were other historical Black role models, not only in journalism, who, as humans had full lives with everything that everyone else had. Even though my life wasn’t perfect—nobody’s is—the laws in place that didn’t want me to be first class did not get in my way of being first class in my heart, head and soul.”

What were those moments ascending UGA's marble steps like for you?

“Hamilton and I were on a mission—not to integrate or desegregate, but to get an education at a school that our parents' taxes paid for. If you look at pictures of us registering for classes, we were singularly focused while walking up those steps. The building is now named the Holmes-Hunter Academic Building.”

As both an objective observer and an active participant, how would you summarize the evolution of Black life since you began your career?

“Objective is a term that I don’t use—only our computers can be objective. As a journalist, I believe in the phrase ‘fair and balanced’ because we are human. I subscribe to Jim Lehrer’s rule to ‘give people good information and they’ll do the right thing.’ Good doesn’t always mean pleasant, it just means that I’ve done my job well, which is a mission that I have pursued all these years, and I will as long as I am able.

“As for Black life, we are people who have every experience that every other human being does. Of course, we experienced successes during the civil rights era and there’s a lot to look at and feel good about. At same time, when we listen to some news, in many instances it’s as if the Black community has never had a moment of challenge in this country.

“The beauty of our history is that, while we have had challenging times since the founding of this country, we have overcome the efforts of those who wanted us to remain objects of discrimination. In the words we grew up with, we keep on keepin’ on.

“It must be acknowledged, however, that there were those who weren’t the same color and believed in, and died for, our freedom, such as Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and Viola Liuzzo. I wrote about them in My People because they are my people. They believed that Blacks should have the same rights as all citizens in this country.”

How do we move forward as a country?

“There’s no question that this is a challenging time; however, many things give me hope. There are people, of all colors, on the case toward more perfect union for everyone. It’s important to note that our country’s founders wrote the word more perfect, not most perfect, because they recognized that humans are not perfect people.

“First, people of color need to be included as decision makers, at all levels, in every level. Black history needs to be taught, in its entirety, from grade schools to college. It’s a cliché, but I believe that we also need younger people to pick up the torch. Lastly, I continue to encourage and promote a coalition of the generations. As I hope My People shows, it’s important for my generation to share our experiences so that the next generation can benefit from what worked and improve on what didn’t. Communication is the key. At every opportunity that I am able, I talk to young people about our history, and I find that its sometimes painful to see how little our history has been taught."

Do you have an example of that you can share?

“While speaking with students at a Florida school, none were aware of the Supreme Court decision that outlawed segregation. On the way to my car, their young, Black teacher confessed that she did not know about it, either—and this is a well-educated woman. The importance of Black history is that it creates empathy and understanding about who we are and what we are entitled to as citizens of this country.”

What can be done on a local level?

“I’m unhappy with what we are going through as a country at the moment. But when we look at history, we've learned what needs to be done from getting feet in the street and educating others about what’s at stake with our democracy.

“Many are receiving misinformation through social media and otherwise. Clear communication is key, now more than ever. It is important for people with a little dough to invest in local media because that is where we are most affected. We need to get, as Jim Lehrer said, that ‘good information’ into our local communities. It could possibly help the divide.

“Then, get out and talk to people on an individual level. We must learn to talk to people who don’t agree with us, which is a challenge these days. Communication is the essence of our existence. In so many ways, this is how we will open doors.”

While compiling the body of work for your new book, what stood out?

“If you look at the reporting in My People, and the Black history within it, it’s true that the past is prologue—we can learn from it and make efforts to fill in the gaps.

“One example is an interview I posted for the New York Times on May 5, 1974, titled "Urban League Director Accuses the Press of Ignoring Blacks." Vernon E. Jordan Jr., who was one of the junior lawyers on my case to integrate UGA and then rose to highest levels of excellence, was the executive director of the Urban League at the time. He said, the press was ‘settling back into the spirit of 'benign neglect' of Black people.’ Jordan went on to say, ‘I thought there would be an outcry from the liberal press about the San Francisco stop-and-frisk dragnet aimed at Blacks. But I didn’t hear a peep out of the big-city newspapers that used to be so concerned about the rights of Black people in the South.’

“Another is a Times article that ran on November 29, 1975, titled "Economist Finds Widening in Black-White Income Gap." It reads, ‘Despite ‘temporary’ gains made by Blacks toward economic parity with whites in the 1960s, recent trends indicate that the gap is once again widening, and that it may be at least 75 years before Blacks catch up, according to one economist.’

“These stories are still relevant now.”

What else stood out?

“I made sure to focus on my ‘sisters’ in South Africa and professional Black women, such as doctors. After all, we are not a monolith—we had and continue to have many kinds of experiences. Often overlooked in coverage are the positive experiences and stories of the Black community and culture.

“This is one of the reasons I was able to convince Arthur Gelb, the influential New York Times editor, to let me open the Harlem bureau. My argument was that we can’t get to know people of the Black community by popping in and out. In the end, he agreed to let me do it. My office was in a Black lawyer’s office at 125th and Seventh Avenues, which was the most popular location in Harlem. So much so that it was called ‘The Corner.’

“Many of the important figures in Black history, regardless of position, would show up to speak on a box or ladder, at one time or another, at this community rallying place. They always drew tremendous crowds. One of those was Charles 37X Kenyatta [Malcom X's bodyguard]. He said, ‘A person who leads must be unwilling to compromise. He must be able to go into the alleys and byways and get those who are not in love with the material things to bring about this revolution. I start here, on this corner, at the crossroads of the world.’”

How have Black women broken through barriers throughout history?

“We can go back to Phyllis Wheatley, an emancipated slave, who was writing poetry from her heart and soul. Like so many Black women, she did not allow society’s view of her to get in the way of being who she wanted to be.

“Also, look at Dr. Dorothy Height, Rosa Parks, Emmett Till’s mother Mamie Till-Mobley, and many others. Thankfully, their stories are getting into popular culture, but they’ve been there for generations. They did not allow white society to shape who they could be. Their history taught them who they could be. It built up their armor and they made history in the process.”

"And don't forget that Black women did not get the vote, even when Black men did. It was years later."

What would you like your white friends or acquaintances to be doing right now?

“I don’t want to separate whites from people of color. I want all of us to be working toward getting this county beyond this challenging time. All people need to work toward the greater good. Educate yourself and get your feet in street.

“I’ll leave you with this. President Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu would often refer to the African word ubuntu, which means ‘I am who I am because you are who you are.’ This saying knows no color and understands that humans depend on connection, community and caring. We cannot exist in isolation.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill.