Does a Classified Sarasota Investigation Hold Shocking Truths About 9/11?

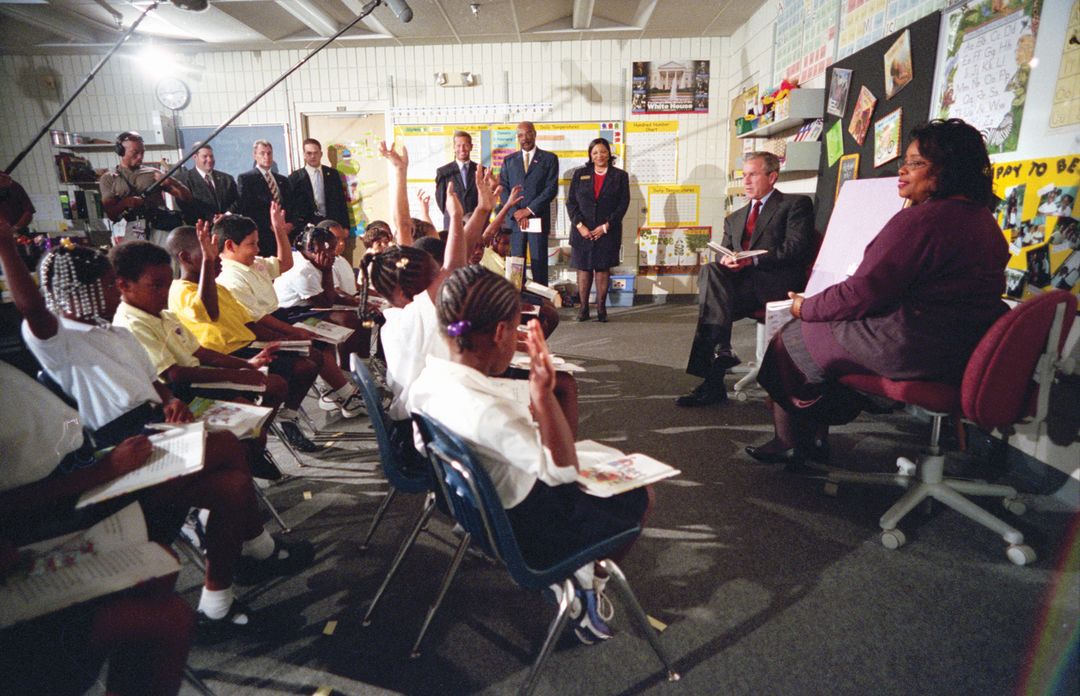

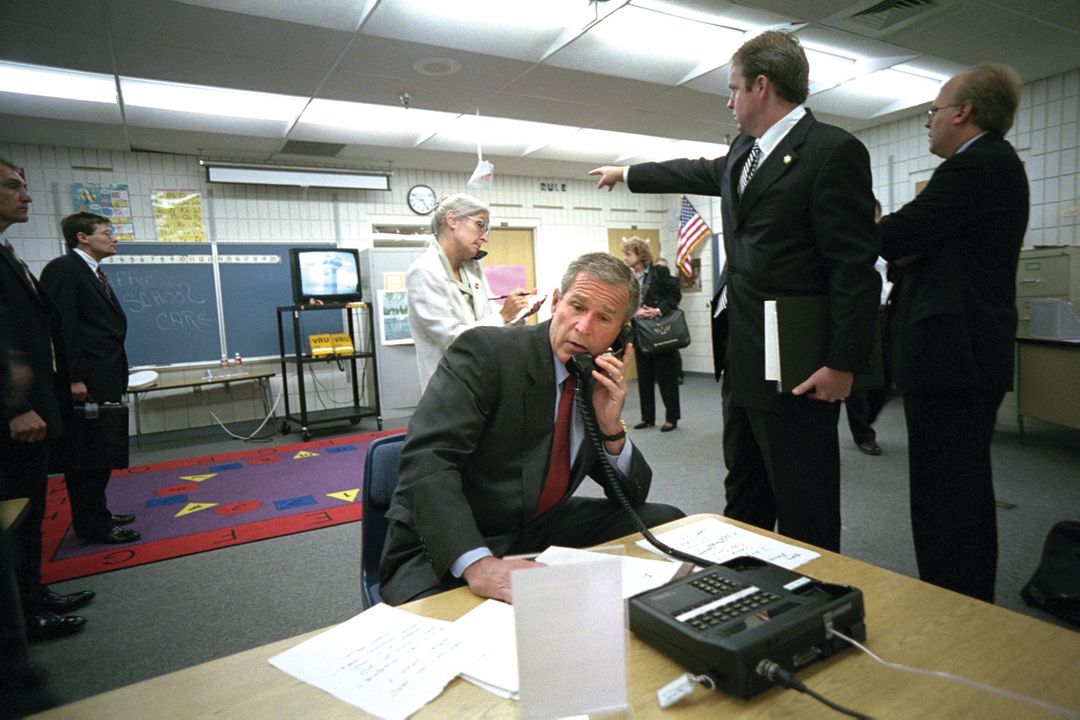

In September 2011, Bob Graham, a former Florida governor who served as United States senator from 1987 to 2005, got a call from an Irish journalist, Anthony Summers, who told Graham he was working with his wife Robbyn Swan on a book about the 9/11 attacks. (Their book, The Eleventh Day: The Full Story of 9/11, was published later that year.) Sarasota figured into that story. Three of the hijackers who had flown planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon had trained at aviation schools in nearby Venice, and President George W. Bush was reading to children at Sarasota’s Emma E. Booker Elementary School when he learned about the attacks. Graham well knew those Sarasota connections, but Summers said he had discovered a new link between Sarasota and 9/11.

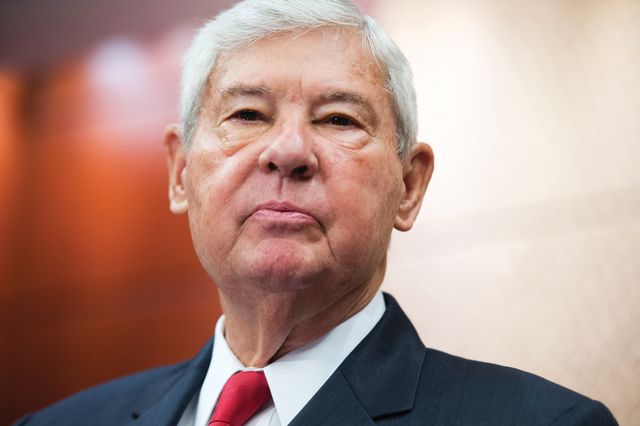

Former Florida Sen. Bob Graham

“He briefly told me about suspicious circumstances in Sarasota,” Graham says, “and he agreed to meet me at the Miami airport.”

At the time of the attacks, Graham was chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, and he also co-chaired the joint congressional committee’s inquiry into 9/11, reviewing more than 500,000 pages of documents and interviewing more than 300 witnesses in 2002. It’s hard to imagine anyone who knew more about 9/11.

As a former reporter and capital bureau chief for the Tampa Bay Times, I’ve covered Graham for years, including reporting on his growing belief that the Saudi government was involved in the attacks. Now Graham and 9/11 are back in the spotlight. In July, he succeeded in his long battle to get 28 pages of redacted material from the joint committee’s report made public; and in September, Congress overrode President Barack Obama’s veto of a bipartisan bill that allows 9/11 families to sue Saudi Arabia for allegedly helping the terrorists. Over a series of interviews this fall, we discussed those developments—and the Sarasota connection to 9/11.

Graham told me he was “surprised” by what Summers told him. “This was new information,” he said.

At the airport, Graham sat down with Summers, who was flying back to Ireland, and Dan Christensen, a journalist with the investigative blog Florida Bulldog. The two said an unnamed counterterrorism official had told them that the FBI’s Tampa office had compiled a lengthy report about connections between the hijackers and a wealthy Saudi family living in Prestancia, an exclusive gated Sarasota community where basketball superstar Michael Jordan once rented a home.

A young Saudi couple, Abdulazzi al-Hiijjii and his wife, Anoud, and their two young twins had lived in Prestancia for about six years before the attacks, the journalists told Graham. Their home, a spacious, one-story Mediterranean Revival-style residence with three bedrooms and a caged pool at 4224 Escondito Circle, was owned by Anoud’s father, Esam Ghazzawi, an adviser to a Saudi prince.

Prestancia, Escondito Circle, 9/11

Image: Everett Dennison

The house was ornately decorated, with Persian carpets on the floors, statues and expensive furnishings. According to neighbors, the family kept to themselves and attracted little attention. (The Bulldog published a story about the family shortly after their meeting with Graham, and the Tampa Bay Times did a follow-up, interviewing a neighbor, Tom DiBello, who said that Abdulazzi was in his 20s and his wife even younger. Abdulazzi was a student and she was very devout, DiBello said. Every now and then, DiBello told the reporter, “He would come over for a cigarette and a drink to get away from that praying every two hours.”)

But two weeks before the attacks, the journalists told Graham, the family left under what Graham describes as “urgent conditions—a new car left in front of the house, food in the refrigerator, and clothes in the washer.” Toys floated in the swimming pool, dirty diapers lay in the bathroom, and clothes and jewelry remained in closets and drawers. An empty safe was open in the bedroom, and a computer cord was still plugged into the wall, but the computer itself had been removed. According to the counterterrorism agent, the FBI had determined that the couple, along with Anoud’s father, had left the United States and were now back in Saudi Arabia, in Riyadh. (According to a later Tampa Bay Times story, Anoud and her mother traveled back to Sarasota in 2003, paying the delinquent homeowners’ fees and arranging for the sale of the house.)

After the attacks, neighbors grew suspicious and called the sheriff and the FBI. A flock of agents descended on the neighborhood, scrutinizing financial documents from the homeowners’ association, interviewing residents and combing through the house. They also examined records of phone calls and of visitors who passed through the security gate. According to the journalists’ source, they uncovered a bombshell: The calls linked the family to the terrorists training in Venice. And the names of Mohammed Atta, the leader of the hijackers, who was a student at Hoffman Aviation in Venice, and two other hijackers, along with Atta’s license plate information, were on file at the Prestancia gate.

Graham, who says he’d long been concerned about evidence suggesting the Saudis may have played a role in 9/11, was electrified by the story. Neither he nor Porter Goss, co-chair of the joint congressional committee, had heard anything about the Saudi family in Sarasota during the 2002 investigation, he says. He contacted the FBI and was told the bureau had provided that information to the committee, but a search of the records proved otherwise.

The FBI had responded to the Bulldog story with a statement saying it had reviewed the Sarasota investigation and found no connections between the family and the hijackers. “That piqued my interest,” says Graham. He asked the FBI to show him the records of the investigation, and the bureau agreed to send them. But no records arrived. So in October 2011, Graham paid a visit to the custodian of the FBI records in Washington, D.C. “He told me he’d never received any requests [to send the reports to Graham], then asked, ‘Would you like to read them now?’” Graham says. He showed Graham two reports; one said there were “many” connections between the Prestancia family and the terrorists and suggested that further trails of inquiry should be pursued.

Since then, Graham has intensified his crusade to uncover more information about Saudi Arabia’s connections to 9/11, connections for which he says there is “voluminous evidence” and which the victims’ families and the American people deserve to know. “I was 65 when I started this and now I’m 79,” says Graham, who estimates he devotes at least a third of his time to this issue.

After the 28 pages from the joint committee’s inquiry were published this July, the White House and CIA director John Brennan maintained they showed no evidence of Saudi complicity in 9/11, and the Saudi foreign minister said they should end any lingering suspicions. Graham disagrees. He says the pages outline more ties to the Saudi government—including that an Al Queda operative had the unlisted number for the company that managed the Colorado estate of the then-Saudi ambassador—and are only the “appetizer” to the feast of incriminating information that is yet to emerge.

After Graham met with the journalists in Miami in 2011, they, along with several other Florida news organizations, filed a Freedom of Information Act to gain access to the records of the FBI’s Tampa office’s Sarasota investigation.

Graham joked to reporters at an Aug. 31 appearance before the National Press Club that anyone filing a Freedom of Information inquiry should also present “a certified statement from an actuary as to what your life expectancy is.” It’s “just incredible,” he said, how the government uses “tactics of delay and obfuscation” to prevent the American people from knowing what their government is doing.

He ticked off the FBI’s various responses to the Freedom of Information request. First the FBI argued it couldn’t release any reports because it would invade privacy. The U.S. District judge in Fort Lauderdale in charge of the inquiry, William J. Zloch, questioned whose privacy the FBI was protecting, since the hijackers are dead and the Saudi family is now back in Saudi Arabia. Next the FBI said it had no written records—a claim the judge also dismissed, after Graham filed an affidavit saying he had already seen two reports from the investigation. Eventually, the FBI produced 80,266 pages of records, which contain information about Sarasota and other investigations and are now in the custody of Judge Zloch, who has been reviewing them, under conditions of intense security, for the last two years.

In July 2015, my husband and I met Graham and his wife, Adele, at Randevu, a small restaurant in Cashiers, North Carolina, halfway between a house he rents and the house where we spend our summers. Over eggs Benedict and cheese grits, he told me more about the FBI’s attempt to cover up the Sarasota investigation, which he has described as growing from a “passive withholding of information” to an “aggressive deception.”

Graham said that in 2011, he and Adele flew into Dulles International Airport on their way to spend Thanksgiving with their daughter in Virginia. Much to their surprise, they were greeted by two FBI agents, who escorted them to an office at the airport where Sean Joyce, the deputy director of the FBI, awaited. Graham figured they had decided to release the Sarasota records. After his meeting at the Miami airport two months earlier, he had tried to contact Gregory J. Sheffield, the FBI agent who wrote the report and had since been transferred to Honolulu, to learn more about the investigation.

Instead, Joyce told Graham they had thoroughly investigated all the events in Sarasota and were satisfied there had been no communication between the Saudi family and the hijackers. It was time, he said, for Graham to forget about this matter.

“You need to get a life,” Joyce declared.

Graham replied that he had seen two of the agent’s reports, which contradicted Joyce’s claim.

“You don’t understand,” Graham says Joyce told him. “That was not a very good agent and we have other information that puts what you read in context.”

“Fine,” Graham responded. “Could I see the information that would put it into context?”

Joyce directed an agent at the meeting to assemble the files and meet with Graham at the FBI’s D.C. office a few days later. But when Graham arrived at the meeting, Joyce was there instead. He told Graham the meeting was canceled and would not be rescheduled. He also told him to stop calling the agent in Honolulu. “I’ve told him not to talk to you,” he said. The agent has since retired and remains silent about the investigation.

Graham told me the Sarasota reports are only part of secret investigations into 9/11 that he’d like to see made public. “I am after the truth and wherever it leads to,” he said.

From top: President George W. Bush at Sarasota's Emma E. Booker Elementary School on Sept. 11, 2001, before and after learning of the 9/11 attacks.

He says the joint committee found information establishing that three of the hijackers who lived in Southern California received support from Saudis living in the United States (despite denials from the FBI that such information existed), and he believes there were additional pockets of support for hijackers who lived in Paterson, New Jersey; Falls Church, Virginia; and Southeast Florida. Fifteen of the 19 hijackers were citizens of Saudi Arabia, he notes. The 19 spoke little or no English and had no visible means of support. To conclude that they carried out the sophisticated attacks on their own, Graham says, “is almost incredible.” (The FBI continues to deny finding contacts between the Sarasota family and the hijackers.)

When asked why Saudi Arabia, an ally of the United States, would have aided the attackers, Graham describes the alliance between the two countries as a “difficult” marriage, fraught with mistrust and suspicion, and historically based on the United States offering protection to the Saudi regime, which is unpopular with many of its people, in exchange for oil.

Saudi Arabia feels vulnerable on many fronts, including aggression from its neighbors, and may want to forge relationships with powers with diverging interests from the United States. Graham speculates that Bin Laden, who had amassed an army in Afghanistan and enjoyed support from extremists in Saudi Arabia, may have threatened the Saudi royals with firing up “civil insurrection” if they didn’t help him in whatever it was he was planning in the United States. The Saudis have an informal network of citizens living in the United States who are charged with monitoring Saudi students here, Graham says, and he believes they were told to assist Bin Laden’s young recruits—whether or not they knew what the recruits planned to do.

Graham says the United States’ reluctance to confront the Saudi involvement in 9/11 springs from several causes. After President George W. Bush stood on the site of the fallen towers and vowed to follow the perpetrators to the ends of the earth, his administration decided that trail led to Iraq. “It was then rather embarrassing to have information flowing in that actually Iraq had nothing to do with 9/11 and Saudi Arabia had a lot to do with it,” Graham told the press club.

Bush, whose family had enjoyed close relationships with the Saudi royals, chose not to act on the information. Graham believes U.S. officials today fear that confronting Saudi Arabia could disrupt their already shaky relationship, and with turmoil in the Middle East in places like Syria and Iraq, they fear they can’t afford to provoke another crisis.

Graham calls this a misguided course that endangers national security. For the Saudis, the conclusion is clear: If the United States possesses compelling evidence that they helped bring about the worst attack in history on U.S. soil and chooses to do nothing about it, Saudi Arabia’s leaders will feel “emboldened,” he says. They will continue funding terrorist organizations and the mosques and madrasahs that are training the next generation of terrorists.

Even more important, says Graham, such governmental secrecy has “a corrosive effect on democracy.” When the government refuses to let its people know what it is doing, he says, they become cynical and suspicious. “We’re seeing it in spades in this presidential election,” he says, and it’s reflected in the low turnout at elections such as the recent Florida primary. “We are developing a democracy of spectators who think their role is to sit in the stands and watch the game,” he says.

Graham notes that it’s not only the FBI, but the CIA, Treasury, State and Justice departments—the entire executive branch of government—that have also suppressed information about Saudi Arabia. “I can understand why George Bush acted the way he did,” he says. “I cannot understand why Barack Obama is acting the way he is. This information is going to be known. Eventually, like the Pentagon Papers, it will come out. The legacy of Barack Obama will be stained when the people recognize that he made the executive decision to restrict [this information] from the American people.”

No one knows when Judge Zloch will finish his review of the 80,000 pages, and only he and the FBI know what they contain. And when some or all of those pages are made public, they’ll likely be interpreted in different ways. Graham believes they’ll paint such a compelling case for Saudi involvement in 9/11 that a public outcry will force further investigation and “a significant recalibration” of the two countries’ relationship.

But the government may continue to insist no connection exists. And some questions may never be answered. If that young couple in Prestancia did assist the terrorists, who asked them to do so, and did they have any idea of the cataclysmic events that would ensue? And what happened that August night in 2001 that led them to snatch up their children and flee, leaving the remnants of their Sarasota life scattered and lost behind them?

Lucy Morgan is a retired reporter and capital bureau chief for the Tampa Bay Times who won a Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting in 1985. Pam Daniel also contributed to this story.