Remembering Snooty

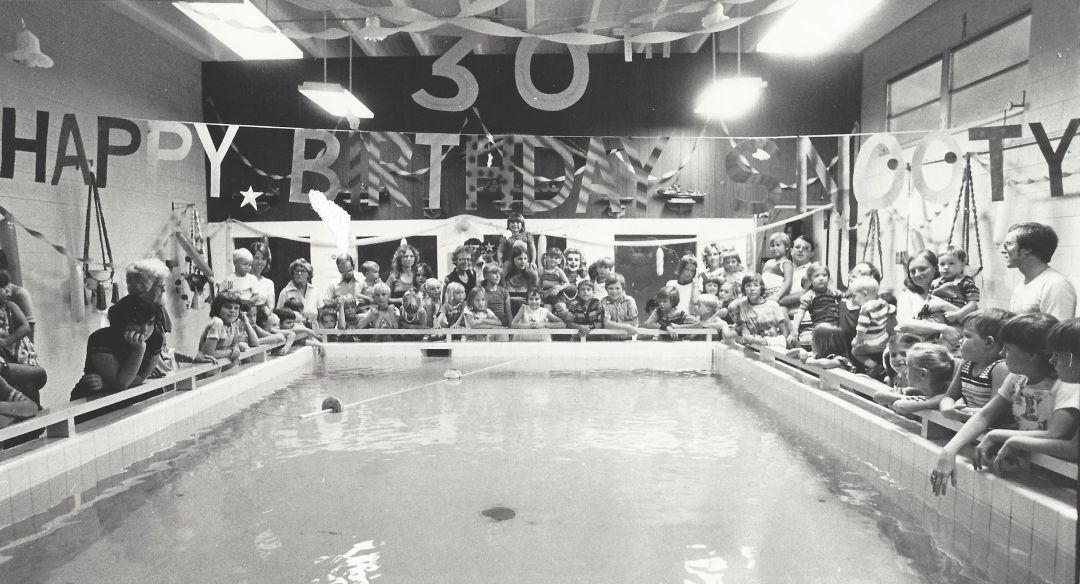

On July 22, 2017, more than 4,000 people showed up at the South Florida Museum ready to party. They were celebrating Snooty, the most famous manatee in Florida, who had turned 69 the day before.

The only performing manatee in the world got a rainbow-layered birthday cake—one made of pineapples, strawberries, watermelon, beets, apples, carrots, celery, broccoli and blueberries. Everyone stood around Snooty’s tank and sang “Happy Birthday.”

For Snooty’s well-wishers, the museum offered cookies and games, art activities and educational displays, and even a guy dressed as Snooty. Eighteen-year-old Foster Swartz of Sarasota had just won the job of being the museum’s suited-up mascot, and he showed off his dance moves.

A day later, Snooty—the real one, not the teen in the suit—was dead. He had drowned in his tank in the dark of night.

Shock and sadness swept through the legion of Snooty fans. No one could quite believe he was gone. New York had the Statue of Liberty, San Francisco the Golden Gate Bridge, and Manatee County had Snooty. Like those landmarks, Snooty had seemed a permanent fixture, something that would never ever go away. But then he did.

Tributes poured in from all over. Fans left heads of lettuce at the museum door. A Bradenton man showed off his Snooty tattoo. Thousands of people signed an online petition to replace Bradenton’s Confederate monument with a statue of Snooty. He was memorialized in newspapers around the world and even showed up as an answer on the public radio quiz show “Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me.”

1949

His popularity—and influence—were immense. Snooty served as a stand-in for all the manatees swimming unseen in Florida waterways.

“He reached millions of people who now have a better understanding of manatees,” says Pat Rose, executive director of the Save the Manatee Club.

Yet Snooty’s birth and life were so different from every other manatee’s that it marked him as a breed apart. Bradenton became his home because of a bureaucratic snafu, and there was similar confusion over his gender.

1958

Snooty was born in Miami aboard one boat after his mother was run over by another one.

The boat where Snooty was born played a key role in the history of Florida. It was originally named the Prins Valdemar, a Danish barkentine that sank in Biscayne Bay at the height of the 1920s building boom. The derelict vessel blocked the entrance to the port for weeks, preventing the delivery of supplies for homes under construction. The accidental blockade helped turn the boom into a bust.

Finally a salvor dragged it to the city’s waterfront. The ship became a struggling restaurant and then a 100-room hotel. Then owner R.J. Walters turned it into the Miami Aquarium, the quintessential Florida tourist attraction. The live exhibits included not only sea turtles, crabs, lobsters, shrimp, sharks, stingrays, alligators and crocodiles, but also showcased a couple of monkeys.

Tourists flocked to see these curious specimens. Visitors included such celebrities as Amelia Earhart, Eleanor Roosevelt, even Ripley of “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” fame.

In 1930, Walters’ aquarium became the scene of the first recorded birth of a manatee in captivity. It wasn’t Snooty, but a calf named Sunny. Mishandling by an employee led to Sunny’s death a year later.

In 1947 a retired manufacturer of women’s wear named Samuel Stout took over running the aquarium, renaming it the Miami Aquarium Tackle Company. Now, in addition to viewing various marine specimens, visitors could also buy live bait.

A year after Stout’s arrival, the crew of the aquarium spotted an injured manatee in the bay.

“She had been hit,” recalled Walters’ daughter, Alice Walters Wallace, in a 2008 interview. “A motor had left deep lacerations on her back.”

The crew netted the manatee, lugged it onto the old ship and lowered it into the largest tank on board. Someone on the staff concocted an ointment for the manatee’s injuries, Mrs. Wallace recalled, “and I would get in the tank and rub it on her back. She liked that. She took to my sister and I right away. We’d get in the tank and hug her. For a manatee, she was a beautiful manatee.”

1978

They named the manatee Lady. Soon they learned that Lady was pregnant.

On July 21, 1948, Mrs. Wallace said, “My dad called and told us the little one was on the way. We came down to see this new baby. He was such a little fella in comparison to his mom.”

At first, they called him “Baby.” The calf turned out to be just as affectionate as Lady, Mrs. Wallace said. When she and her sister would climb into the tank, “Both liked to be loved and petted. They liked to give kisses.”

To entertain tourists, the girls would ride on Lady’s back—but never Baby’s.

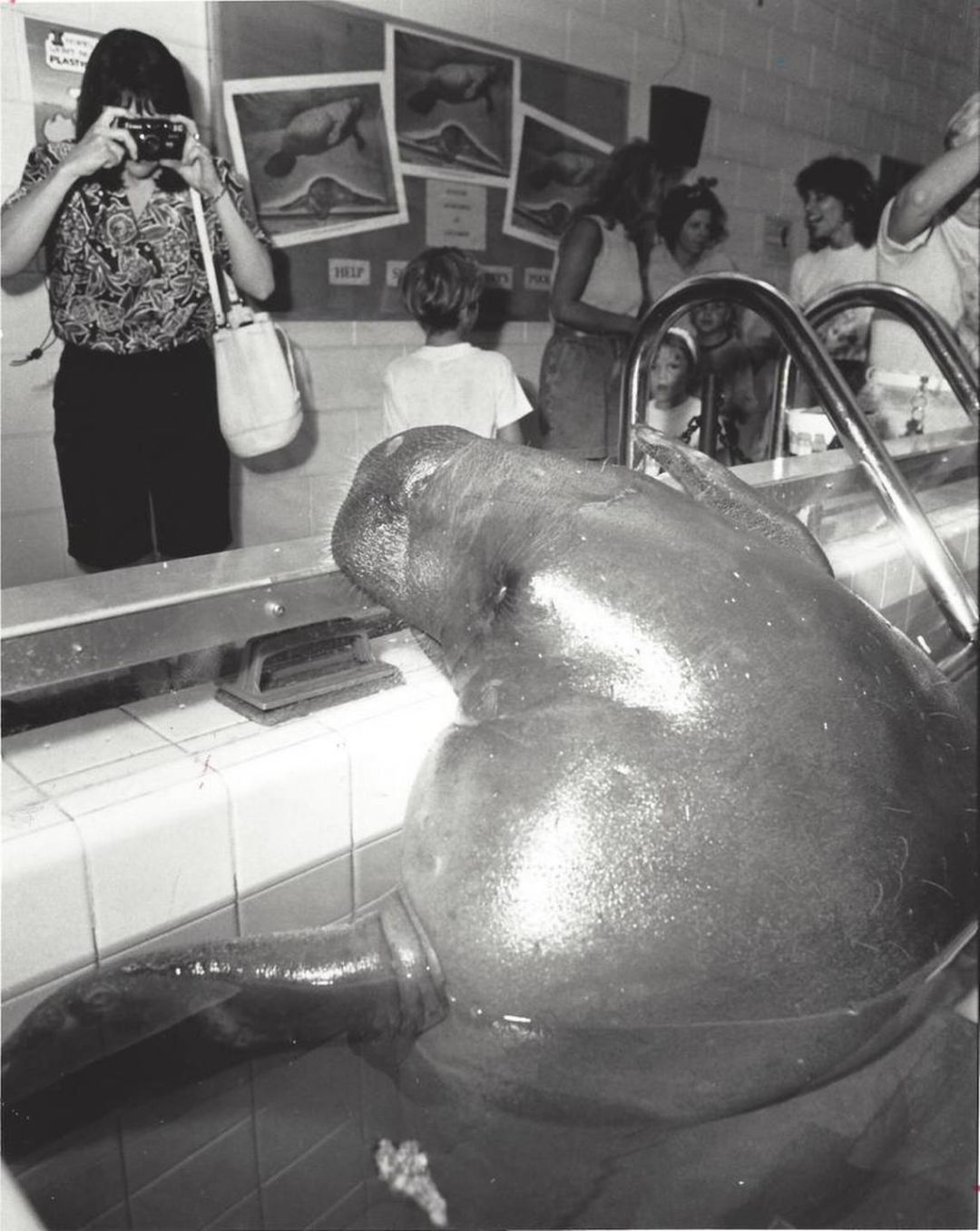

Sam Stout taught both manatees a few tricks. They learned to come when summoned, to roll over in order to get a treat, and to hoist themselves out of the water to nuzzle noses with a human. Biologists later pointed to those tricks as evidence that manatees are smarter than they might appear.

Although Baby was a big attraction, when some people on the other side of the state needed a manatee, Stout put the calf in his truck and took off for Bradenton.

1992

Manatee County is designated by the National Park Service as the spot where conquistador Hernando de Soto set foot on dry land in 1536. The annual De Soto Heritage Festival in Bradenton celebrates not only de Soto’s landing but also the subsequent settling of the region by Josiah Gates in 1842. The early settlers named the county after “the gentle sea cow, or Manatee, seen so frequently in the area’s numerous waterways,” according to the Chamber of Commerce.

The 1949 “De Soto Celebration,” as it was known then, promised to be an extravaganza. But a week before the March 22 start of the celebration, no one could locate a single sea cow to put on display.

“Our name will be MUD without the Manatee,” one of the festival’s organizers wrote.

Finally they persuaded a Miami politician to use his influence to get a state permit for Stout to bring a manatee to Manatee County. State employees even helped Stout design the special tank for his truck. As Stout drove across the state he stopped frequently to change the water in the tank, drawing a curious crowd every time.

At the festival, he displayed the 9-month-old Baby, which “gave pleasure to thousands of people who had a chance for the first time to see the animal this county was named for,” a local official wrote. “It was a great favorite with children and hundreds of them petted it, fed it lettuce, and watched it roll over.”

The event, however, backfired for Stout. One of the festival’s publicity “experts” spread the rumor that Stout had used a harpoon to capture manatees. The Humane Society and Audubon Society protested this cruelty to the state conservation board.

State officials reviewed their records. Stout had a permit for one manatee, yet somehow owned two. He was ordered to let Baby go. Stout was horrified. Baby would die, he said.

He came up with a solution: He would donate Baby to Manatee County. The state said yes. Only then did anyone think to ask Manatee County officials if they wanted a manatee.

“Bradenton learned with some consternation today that it owns a sea cow,” the Bradenton Herald reported on April 1, 1949. Eventually, though, city officials embraced their mascot, installing a tank in the part of the Chamber of Commerce building that housed the original South Florida Museum.

The Miami Herald, writing about Baby’s imminent departure, joked that “the youngster probably has an inferiority complex by now, the way she has been treated in recent months.”

Note the pronoun. Everyone had assumed Baby was female. At some point, someone figured out the young manatee was a he. The name changed, too, going from “Baby” to “Baby Snoots”—apparently a corruption of Baby Snooks, a popular radio character. Around 1970, when he was in his 20s, he finally became “Snooty.”

As for Lady, when the Miami Aquarium closed in 1950, the only other performing manatee in Florida was released back into Biscayne Bay. Snooty’s mother was never seen again.

As the years rolled on, Snooty became a treasured institution. Visiting Snooty and seeing him perform tricks became a rite of passage for generations of children.

In 1973, a clumsy tourist dropped a mechanical pencil in Snooty’s tank. Snooty swallowed it and became constipated for more than a week. News reports warned that he might die.

“If he dies,” one report intoned, “the museum will have lost its main attraction. Manatee County will have lost the embodiment of its name.”

Snooty survived the Great Pencil Scare. He also survived being raised in a too-small tank, which biologists said stunted his growth (he got a larger one in 1993).

A greater concern was solitude. Snooty was spared the fate of many manatees, being clobbered by boats or poisoned by red tide. The price he paid was celibacy and isolation.

In 1991, when Snooty turned 43, the Save the Manatee Club and the Humane Society demanded he be moved two hours north to Homosassa Springs State Wildlife Park. There he could meet, and perhaps mate with, seven breeding-age females.

Snooty’s solitary captivity is “the most depressing manatee story around,” the club’s president told the St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times). But Snooty’s chief keeper, Carol Audette, warned that moving Snooty in with other manatees might be bad for him.

“He’s so acclimated to people,” she said. “That’s all he knows.”

Bradenton was bombarded with angry letters from around the country demanding Snooty be released. But Snooty’s captivity pre-dated the Endangered Species Act, leaving no legal grounds to challenge it, and he remained at the South Florida Museum.

In 1998, his isolation ended. He started getting roommates—male manatees that had been injured in the wild and needed time to recuperate. According to Save the Manatee’s Rose, Snooty welcomed the newcomers, playing big brother and showing them how to behave around people. The manatee menagerie drew more visitors, who eagerly paid for Snooty T-shirts, postcards and plush toys.

Not all those injured manatees survived, but Snooty kept going, year after year. He maintained his vegetarian diet and got plenty of exercise swimming around in his tank.

David Murphy, his longtime veterinarian, says he had no obvious health issues beyond developing what Murphy called “the Snooty Sag”—just like other geriatrics who lose their skin tone. Three or four years ago Snooty went through what Murphy termed “a little spell” where he lost weight “and was kind of in a downward slide. And then he rallied about two years ago and he looked great ever since.”

At his most recent check-up, Snooty’s teeth and heart were in great shape, and he weighed a healthy 1,300 pounds, Murphy said. He also still had a healthy reproductive system, but after the 1991 crusade, no one tried again to help Snooty hook up with a female.

Surprisingly few manatees live in captivity, and day after day, Snooty set new records for how long a captive manatee could survive. Manatees’ closest evolutionary relatives are elephants, which live to be 80, so Snooty probably could have kept going for another 11 years. Murphy figured someday a progressive disease would claim Snooty. He was wrong.

Around the time of Snooty’s birthday celebration, the bolts to a panel that accessed a plumbing area in his tank came loose. After the party was over and the museum was dark, the panel somehow came open. All four of the curious manatees in the tank could get inside the plumbing area, but only three were small enough to get out again. According to museum officials, Snooty got stuck and drowned. They have invited outside experts to investigate further.

“It was unfortunate the way he died,” Murphy says, “but in the big picture, he lived an amazing life for a manatee, swinging between the human and manatee worlds.”

As with all manatees that die in Florida, Snooty underwent a necropsy at the Marine Mammal Pathology Laboratory in St. Petersburg. But Martine deWit, who oversees the lab, said that even in death, Snooty won’t be like the other manatees.

“He won’t go into our database” of manatee deaths, she said, “because he wasn’t part of the wild population.”

A day of rememberance for Snooty will take place from noon to 5 p.m. on sept 10 at the South Florida Museum. Admission is free.