Longtime Human Resources Executive Mirian Graddick-Weir on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

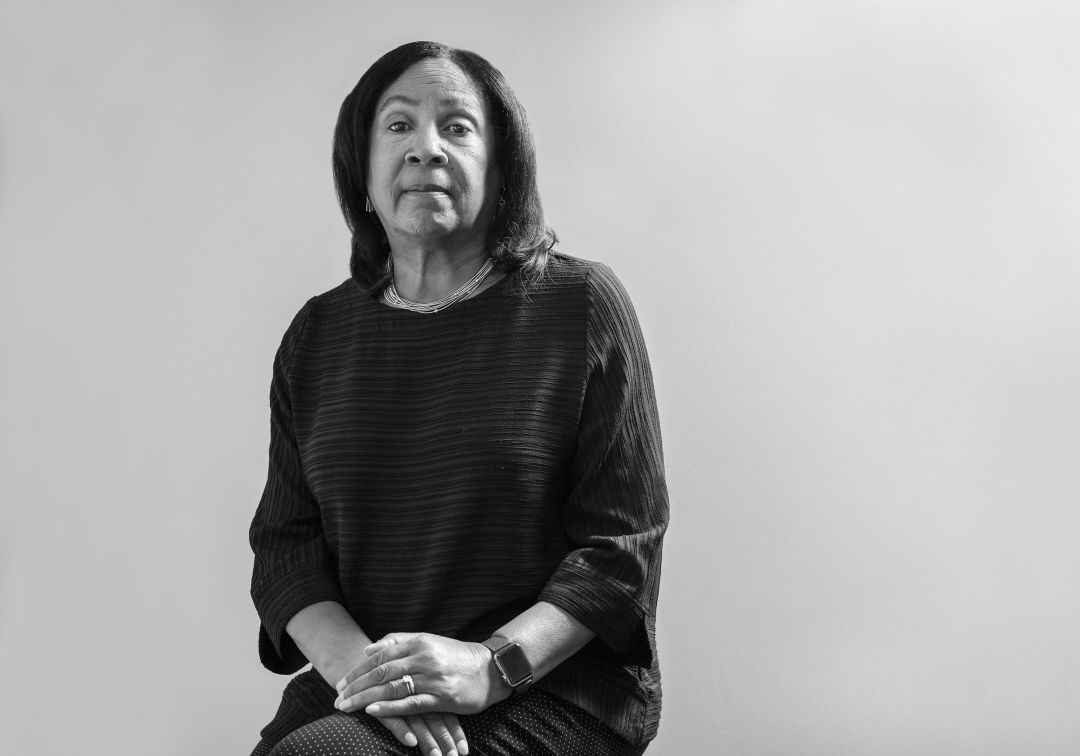

Mirian Graddick-Weir

Image: Michael Kinsey

Born in Rantoul, Illinois, human resources executive Mirian Graddick-Weir was raised at Air Force bases around the world as the child of an enlisted father. Throughout her life, she shattered glass ceiling after glass ceiling. She was the first Black person to graduate with a Ph.D. from the industrial/organizational psychology program at Penn State University; the first Black woman to be elected as a distinguished fellow of the National Academy of Human Resources; the executive vice-president of human resources and employee communications at AT&T; and, until her retirement in 2018, the executive vice-president of human resources for Merck & Co., where she led all aspects of the organization's human resources department and was instrumental in her colleague Ken Frazier's transition from general counsel to CEO.

Graddick-Weir has also been recognized by Black Enterprise as one of the 50 Most Powerful Women in Business, and by Human Resources Executive magazine as one of the most influential global HR executives.

In 2016, in honor of her late father, Dr. Samuel Massenberg Sr., the former director of education at NASA, Graddick-Weir and her husband Dr. Michael J. Weir established the Samuel E. Massenberg Sr. Foundation to advance educational opportunities for people of color in the STEM fields.

Today, at 68, Graddick-Weir is retired and continues to give back not just through her foundation, but also by serving as board member for YUM! Brands, Inc., Booking Holdings, Inc. and the Society for Industrial/Organizational Psychology. She is also the president of Weir Group LLC, a management strategy consultancy firm that Michael founded. The couple split their time between Sarasota and Martha’s Vineyard.

What was it like moving from military base to base as a child?

"I remember the kids coming together at the bases, and we all knew it was temporary. Looking back, at times I craved growing up with a best friend, their families, and the families in a neighborhood—or even having the opportunity to have a memory of, say, my favorite third grade teacher.

"On the other hand, moving helped me developed a skill that has been important in my life and career, especially in a global company. It’s easy for me to get out of my comfort zone and move into various cultures and opportunities. I can comfortably navigate ambiguity and uncertainty."

When did you first realize that you were different because of the color of your skin?

"My mom enrolled me at a Catholic school in Germany, where we lived from 1961-1966, which was all white. I remember my first day of third grade, she rode on the bus with me. I was clinging to her until she left. My first experience alone was in the cafeteria, where I was the only Black child, and every single kid turned to stare at me.

"There was no harm or anything mean-spirited, but this was my first time experiencing that I was different, and not in a good way. I know that I was the talk of everyone’s home that evening. Prior to school, I had learned a little German and I knew that ‘schwarzes mädchen' meant ‘Black girl,’ a term that I would hear around school. I remember how isolating it felt."

Tell us about your parents.

"Both of my parents grew up in Detroit. When my dad met my mom, he was on a weekend pass from the Air Force, and she was a nun in a convent.

"My mom was incredibly bright, but she sacrificed her career to raise us and follow my dad as a military spouse. Being a former nun, it’s not a surprise to me that my mom was one of the kindest people I’ve ever met. When I read books about kindness, I chuckle because she could have written one. She was the epitome of empathy, and ‘do unto others’ was her motto in life. Even in adversity, she was kind."

How about your dad?

"My dad had passion for flying before he even got in the cockpit. One summer when he was a teen, he approached a Black man named Neil Loving, who was a pilot and owned a small private airport in Detroit. Mr. Loving told him, ‘I can’t afford to pay you to wash planes, but I can teach you how to fly.’ After only six hours of instruction, my dad flew solo between Detroit and Indianapolis. Today, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., displays one of Mr. Loving’s planes.

"My dad dropped out of Wayne State University—he later completed his degree at Ohio State University and got his doctorate at Virginia Tech—to join the Air Force and flew a B-29 Bomber during the Korean War. He was the only Black man in his flight group. During a training mission, his plane was shot down. He parachuted out when it caught fire, then lived in caves until he was captured and put into a prisoner of war camp. Because his gloves were in the plane [when he got shot down] my dad got frostbite on his fingers and his ring finger on his left hand was amputated in the camp. He was 6’3’ and when he left for Korea, he was 175 lbs. After eight months in the camp he returned at 100 lbs. Ultimately, he was grounded because he didn’t have feeling in his hands.

"I learned so much from him. He was a role model in terms of bravery and courage."

What did your father do after the military?

"Dad took a job teaching science, technology, engineering and mathematics [STEM] and mentoring cadets at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. After he retired from the military, he became dean of men at Hampton University, a HBCU. He wanted to be a part of mentoring and coaching the incredibly bright and talented Black students there. He didn’t have a lot of role models in his discipline growing up, and he wanted to give back.

"After that, he went to NASA and worked in education and training at Langley. A lifelong learner, he and I got our doctorates in the same year.

"When he passed away, I was amazed by number of the former students who showed up to speak at his funeral and how he changed their lives."

How did you choose your college?

"My dad was the one who encouraged me to go to Hampton University, where he worked, because we spent five years in Germany, so I grew up in a lot of white situations as the only Black person. He wanted me to have the Black experience; to have pride in who I am and be exposed to the many highly educated Black people in the world.

"It was a different transition. There was a level of pride in being with people who look like you. Afterward, I went to Penn State, where I had the opposite happen. Days would go by when anyone would barely speak to me."

Condoleezza Rice once said, "I think those of us who grew up in segregation were able to spot at 100 paces when somebody was underestimating you.” What do those words mean to you?

"Often, we are in situations where we must constantly prove ourselves because it’s not assumed that we are intelligent enough to contribute to the conversation at hand—specially when the room is predominantly white.

"We know that they are wondering how we got there. We can also spot a surprised reaction when we contribute a good idea or finish a terrific presentation. We are largely underestimated.

"For me, there’s also the added burden that we must work harder, burning unnecessary energy trying to show just the right balance of competency without being too pushy, but also being prepared and proving that we can do the job."

You and your husband Michael launched the Samuel E. Massenberg Sr. Foundation in honor of your father. Tell us about the meaning behind the organization and its mission.

"After my dad passed away, we wondered how to honor someone with his military career, tenure in training and education, and dedication to advancing people of color in STEM. This is a man who created a summer scholarship and internship program at NASA that was recognized by the Princeton Review as one of the top internship programs [in the country]. My father saw firsthand how STEM internships and scholarships changed lives for people of color.

"With that in mind, Michael and I created the foundation with the simple mission to increase the number of people of color, primarily Blacks, interested in pursuing STEM degrees.My husband discovered that even though Blacks and Latinos declare STEM as a major proportionally to whites, only 40 percent end up with the degree. This could be due to many things, from lack of role models to lack of supportive environments. But if we capture students early enough, we can show then how fun science can be and help them be competitive.

"We partnered with Chancellor Kumble R. Subbaswamy and Dr. Laura Haas at the University of Massachusetts Amherst to create a summer camp. It is the perfect partnership, and the incoming chancellor, Javier Reyes, is equally committed. Our focus is to recruit public school 10th graders from New Jersey and Massachusetts through guidance counselor nominations.

"The two-week camp launched in 2019 with 16 students. Every year since, we've opened the camps with a panel discussion that includes Michael and me explaining who Dr. Massenberg is, his history and passions, and what his expectations of them would be. We also share why it’s important for Blacks and people of color to enter the STEM discipline from an innovation standpoint— especially considering what we learned about healthcare disparities during Covid. Then I tap into my experience at Merck—the challenges of getting people of color in clinical trials and why we need people like them in the field as a part of the talent, as role models and as representatives for Black people. My dad would be so proud."

Many companies have made a commitment to racial equity since the summer of 2020. In terms of human resources, what should that pledge look like internally?

"This question hit a chord for me. After the George Floyd murder, many CEOs made commitments that sounded like sound bites. From a HR perspective, my fear was that it was either for publicity or that they made promises without understanding their organization’s culture—it is easy to make them in the moment. For instance, do company leaders know where the gaps exist—from a representation standpoint, especially in the senior ranks—so they could put realistic goals and metrics in place to make progress in racial equity over time? Many companies invested so much money in diversity, equity and inclusion [DEI] programs, but didn’t get at the systemic issues."

How does company leadership do that?

"In my opinion, there are three planks to achieve racial equity. At Merck, we looked at gender and racial groups—Blacks in particular. Where was the representation good? Then we found the critical points in the funnel where that representation dropped off and asked why. We wanted to know what was happening, because that was the beginning of the problem. HR departments need rigor and analytics to dissect and understand issues, whether they’re recruitment or attrition. This allows for metrics to be put into place that hold people accountable for closing the gaps over periods of time. That’s the first plank.

"The second plank is equity itself. Many companies are looking at pay equity across race and gender. There are tools available to analyze if everything is equal—so why is there still a discrepancy in pay? Some companies are beginning to remediate and pay higher bonuses or salaries in order to close the gaps.

"Now, even if they close the pay equity gaps, that doesn’t mean that people have equal access to opportunities within company. You must ask, 'What’s your promotion rate? How many Blacks are in critical roles? How many Blacks are succession candidates?' That’s where you peel the onion. If people of color don’t have equal access to opportunity, then you can’t achieve racial equity.

"The third plank is inclusion. Even if you happen to have representation and role models, if you bring people in and they feel like they don’t belong, or they look up the ranks and don’t see people who look like them, or they don’t feel their voices are heard, then you haven’t created an inclusive environment and they will ultimately leave. Also, it’s important to dig around in engagement and culture surveys. Do Blacks feel like they belong? Someone told me that diversity is being invited to the party, and inclusion is being asked to dance. If employees are sitting around a table and not being heard, you’re not allowing them to live up to their full potential.

"Diversity, equity and inclusion is a constant journey without a destination. You must work at it every single day and there must be a sustained commitment at the top of company that permeates throughout."

What would you like your white friends or acquaintances to be doing right now?

"As Stephen Covey said, ‘Seek first to understand, then to be understood.’ Listen and learn, particularly from people with different lived experiences. After George Floyd’s murder, that was the first time that an authentic and transparent conversation happened. Employees who worked in companies for years were candid and CEOs were listening. I’m on two boards that went out on listening tours. Afterward, I could tell that these weren’t just surface conversations. They were meaningful.

"Also, it’s important to read history because it’s an important context. I’m currently reading Driving the Green Book by Alvin Hall. The Green Book was put together by the Greens, who edited it every year—it was a wealth of information for Blacks traveling between the north and south so they would know how to be safe during Jim Crow.

"The reason I recommend this for a white person is because it would be helpful to understand what it means to be ‘driving while Black.’ People were petrified to get out of cars at gas stations back then. Fast forward to today: Black people are still counseling their sons on what to do and to say so nothing bad happens to them. History helps understand why there’s bitterness and resentment in the world, but also why you don’t repeat it. It also explains why some are discouraged, tired and worn out.

"Lastly, be proactive in dismantling policies and practices. Be an advocate for racial equality. It’s not good enough anymore to grumble from the sidelines. You must get involved. When you’re around people who are different from your lived experiences, and you are open to listening and learning, you get to know them in a humanized context. They may be different from what you've heard or read or the biases that you’ve been exposed to. The more we can create situations where you are exposed to people of different backgrounds, the more we can work together for common goals and some of the barriers will come down.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill