Sal Serbin on What It's Like to Be Native American in Sarasota

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

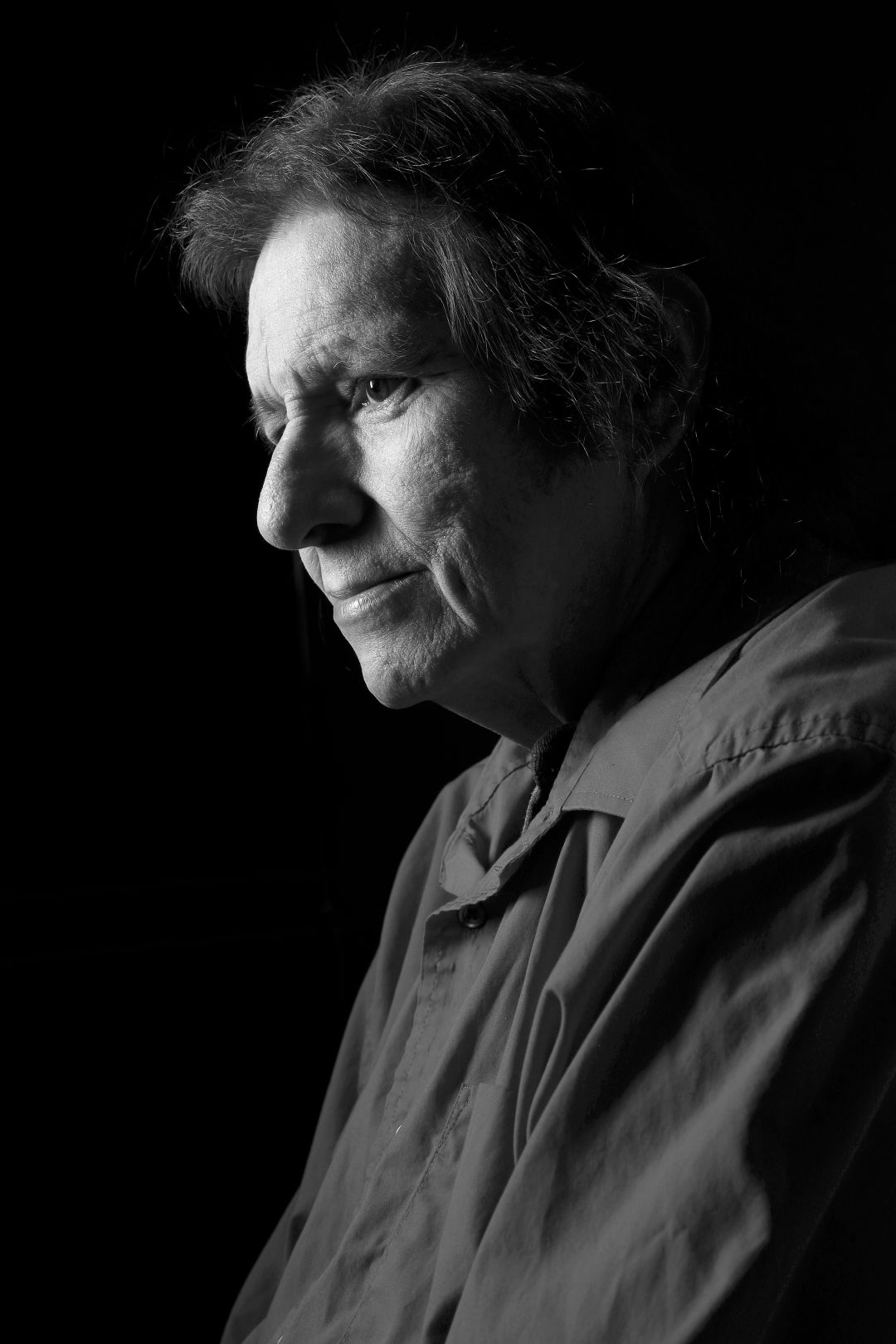

Sal Serbin

Image: Salvatore Brancifort

Sal Serbin is a Native American from the Assiniboine (pronounced "ah-SIN-uh-boin") tribe in Poplar, Montana. He’s lived in Sarasota for more than 20 years and works as a radio host at the community radio station WSLR 96.5, where he hosts a weekly show called Indigenous Sounds. There, he goes by his native name “White Horse” and talks with Native American chiefs and activists. He plays traditional Native music, informing listeners about his people and the challenges they face.

Serbin says he has encountered prejudice in his place of work and on the street and even among other minorities in Sarasota. This November, in honor of Native American Heritage Month, Serbin hopes that more people find ways to support his “forgotten minority.”

Can you give us some background on your heritage?

"I belong to the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes that are in Poplar, Montana. The Assiniboine have lived in the Great Plains region of North America for thousands of generations and used to be part of the Great Sioux Nation, a congregation of more than seven tribes throughout America. I still have family that live on the reservation in Montana, and many Sioux live on Pine Ridge Reservation, located in South Dakota. I lived in Montana until 1967, and my mother moved us to College Park, Georgia, to give us a better life."

What is life on the reservation like?

"Life on the reservation is different for every tribe, but there are many tribes that live under extremely poor conditions. Many reservations lack running water, electricity and government support. Many Natives struggle financially and find themselves isolated from the outside world.

"My mother did not want this kind of life for us. She also didn’t want us to be forced into residential school, as she was as a child. Residential schools were government-supported schools run by Christian missionaries until 1975 in the United States. Missionaries would take in Native children and force them to assimilate to the ways of Euro-American culture, or 'the white man.' They would be forced to speak English, practice Catholicism instead of their traditional spirituality, wear Westernized clothing and even have their long hair cut short. Long hair is an important symbol in our culture. By doing this, they stripped away everything that made these children Native."

What were the challenges once you moved off the reservation?

“At the time, we thought we’d escaped the hardships we faced on the reservation, but we ended up facing a whole new challenge—racism. We were living in a town in the Deep South, closer to Alabama, and I witnessed several Klu Klux Klan rallies in my neighborhood. There were racially charged signs planted all over town. They were not just prejudiced against Blacks, but against any minority.

“As an adult, I took over my mother’s Native American general store that she owned in Georgia. I would host traditional pow-wow ceremonies. One time, the Klan came and stomped it out. I ended up getting them to talk to me and remove their masks. Some of the men rioting against me were men I worked with at the local power plant. This was explicit, overt racism, from people I knew. It was astonishing.”

Did you move to Sarasota to escape racism?

“My wife and I moved to Sarasota in 1998, when she became pregnant, because she was dealing with prenatal complications. Our research determined Sarasota Memorial Hospital had some of the best OBGYNs, so we moved here to see if she’d get well. We also figured it would be a good change of pace."

Did you find a more welcoming environment in Sarasota?

“There have been several times where strangers shout at me from across the street, telling me to 'go back home to where I came from.' Natives have a warrior spirit within them. We are not typically afraid to speak up for our kind. So, I usually tell them, 'My ancestors’ bloodline has been on this land for thousands of generations before you. I’m Native American. This is the only home I’ve ever known.' My response catches people off guard.

“I’ve also experienced racism in my workplace. At [one place of work], I’ve had [someone] get into my face in a meeting and begin chanting and covering their mouth repeatedly with their hand. Not only was this extremely uncomfortable for me, but no one else in the room even batted an eye. It’s a false stereotype against Natives. We do not chant like that. I wanted to confront him but felt I could threaten my job. So, I kept quiet."

You eventually received an associates degree in legal studies and worked as a paralegal. One of the lawyers you worked for focused on Indian Law.

"Yes, Indian Law isn't even acknowledged by the Supreme Court, but it's where lawyers help out reservations with anything they may need. We'd stand before Congress and testify on occasion, for improving reservation conditions and Native American safety. Back then I hated the government. I saw corruption firsthand as a paralegal. I even experienced racism against Natives. The government doesn't even want to acknowledge us sometimes."

What do you think about school mascots using Native American names?

“Venice High School’s mascot has been the Indians since its establishment, and I believe it should be changed to something more culturally accurate to our area. Some students have created merchandise [T-shirts and banners] with the slogan, 'Angered Indians,' which further perpetuates the stereotype that Natives are violent, angry people. The school board refuses to put the issue on the agenda and vote to keep or change it. We are peaceful, and our traditions and spirituality are rooted in peaceful practices. The Ringling Redskins youth football team has yet to change its name after being told it is offensive. People just don’t see it that way.”

How do you try to inform people?

“I’ve tried to speak at local anti-racist groups in town, one of which was prior to the Covid-19 pandemic put on by Fogartyville and the local Peace Coalition. But several members of a local organization [representing minorities] pushed their agenda and did not want to hear about the issues Natives had with the offensive team names in town, and fake festivals and pow-wows put on by fake tribes in the county and state.

“At one of these meetings, I was told to stop complaining about my people’s issues. I felt my safety was at risk in that moment, and I was alone. It makes me sad, because, as minorities, I believe we should be working together toward equality.”

You've also said the media usually doesn't cover Native Americans accurately.

“When we are noticed by the media, we are portrayed as an intimidating, violent people. But most of the time, we are not even recognized by the media.

"An example of this was during the murder case of the North Port white woman Gabby Petito. While law enforcement searched for Petito's body, hundreds of Native American women's bodies were found in Wyoming, where Petito went missing. In the last 40 years, more than 2,000 Native women have disappeared in the United States, several of which were never reported to police."

What are some of the most common examples of misusing Native American culture?

“Our traditions are appropriated, such as the use of our traditional regalia [headdresses, feathers and fringe] by people claiming to be Native when they are not. There are more than 50,000 fake tribes in the United States, as opposed to 570 certified ones. Each time these fake tribes perform a traditional dance incorrectly, like at local pow-wows put on by the Native American Indian Festival last year, or wear the improper dress, they are educating with false information."

What are some changes that you are hoping to see in our town and country toward Native American people?

“I would like to see more people recognizing Native American Heritage month, more businesses, more individuals and more organizations. The Biden Administration announced November as the official celebratory month, but not many people have brought attention to it yet. We finally get a whole month to share our traditions and stories of how we’ve been whitewashed out of American history. We are basically the forgotten minority.

“I hope schools will begin teaching children the real story of Thanksgiving. The feast was not how it is celebrated today. We helped colonists learn to live off the land, or they would die. But then, they turned around and started killing us off. We were moved into reservations. We were controlled.

"I hope that more Natives feel empowered to speak up and work together to see laws change for the betterment of reservation conditions and Native rights. I work with fellow local Native American Joelle Clark from the Oglala Sioux tribe to raise funds for reservation improvement nationwide, for Indigenous People’s Day to be celebrated every Oct. 10, and for Native people to feel comfortable fully expressing their heritage in whatever capacity they desire—whether through spirituality, dress or traditions."