Proposed Aquaculture Facility in the Gulf of Mexico Draws Opposition from Sarasota Environmentalists

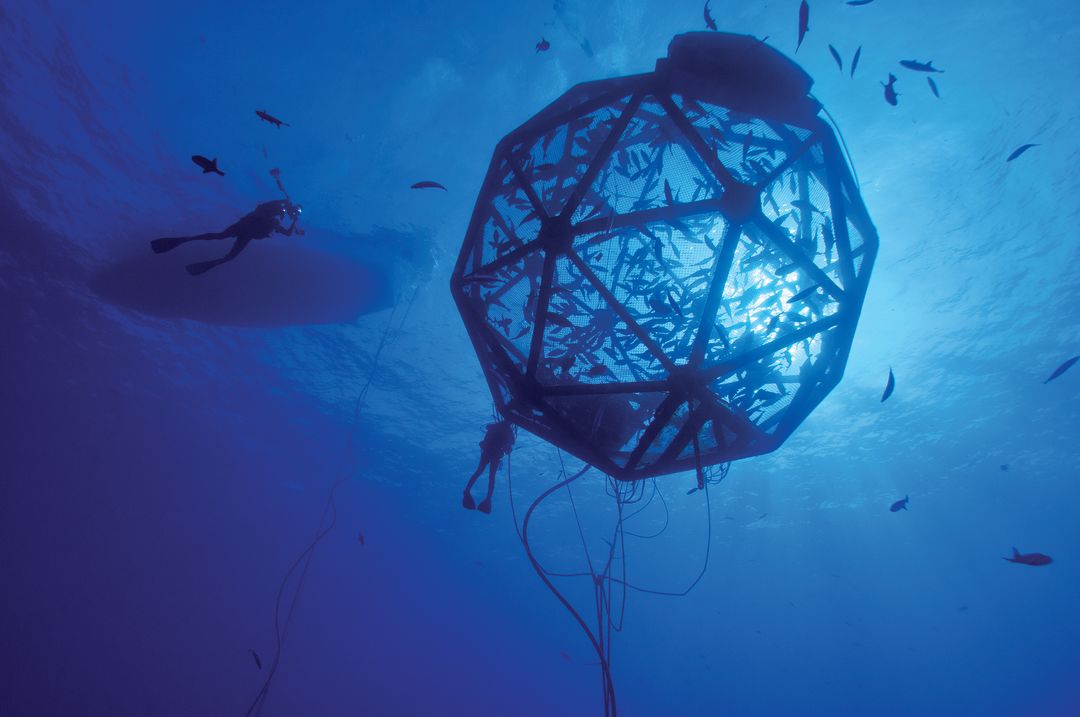

An Ocean Era Aquapod located in the waters around Hawaii.

Image: Rick Decker

Back in 2016, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration finalized a long-in-the-works plan to manage the construction of aquaculture facilities in areas of the Gulf of Mexico controlled by the federal government. But there was a problem. The regulatory hurdles were so complex that no company wanted to apply for the permits needed to build a fish farm—until Ocean Era came along.

The company, which is based in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, has already developed two aquaculture projects in federal waters, raising kampachi, a fin fish known around the Gulf as almaco jack. In 2017, the company became the first entity to try to build an aquaculture operation in the Gulf when it announced plans for Velella Epsilon, a kampachi fish pen to be built about 40 miles west of Sarasota.

The facility is pitched as a pilot project—a small first step that will allow Ocean Era to demonstrate that aquaculture in the Gulf can work. The main component of the facility will be one of the company’s Aquapods—a huge, floating, ball-shaped pen that will be anchored to the floor of the Gulf. The Aquapod will hold 4,000 fish that will be fed five times a day.

“With our experience, we felt a moral responsibility to be a pioneer in this,” says Neil Sims, Ocean Era’s chief executive officer. He ticks off a number of pressing environmental crises: rising global temperatures, ocean acidification, coral bleaching, dwindling freshwater resources and growing meat consumption. “Most of these things can be addressed by humanity starting to move toward more marine-based food sources,” says Sims. “We’ve got to get more of our food from the sea.”

The National Aquaculture Association estimates that the United States imports 90 percent of our seafood, and roughly half that comes from farms. Many aquaculture fish are fed fish meal, which increases the industry’s effect on fish stocks. Approximately a quarter of all fish caught in the wild end up as fish meal used to feed other fish. To reduce that footprint, Ocean Era uses a feed that is made with soy protein concentrate. According to the company, kampachi fed 40 percent soybeans are indistinguishable from fish given a normal fish meal diet.

A coalition of local and national environmental groups, however, is skeptical of the company’s plans. The Sarasota nonprofit Suncoast Waterkeeper has challenged the company in court, and organizations like the Sierra Club and the Center for Biological Diversity have joined the opposition.

Kampachi in an Ocean Era fish pen

Image: Ocean Era Inc.

They charge that fin fish aquaculture is too risky for the Gulf. They warn that existing marine species could be affected by so-called “fish spills,” when fish escape pens, as well as diseases and parasites that can proliferate in aquaculture operations. Antibiotics and other toxins, as well as effluent from the fish’s feed and waste, can also harm the Gulf, they say, and the growth of aquaculture could also threaten existing commercial fishing businesses.

“Any time we are industrializing our food system, it is a problem, whether it’s on land or in open water,” says Suncoast Waterkeeper executive director Samantha Gentrup. “It’s unnatural.”

Waterkeeper founder Justin Bloom says waste from the facility could worsen red tide. “It’s in a pinch point area where we know red tide originates and develops,” says Bloom, “and the amount of nutrients that are going to be produced is significant. That type of nutrient pollution is fuel for red tide.”

Sims says effluent from aquaculture operations close to shore can indeed hurt the environment, but that the Ocean Era facility will be located far enough offshore that the waste will be dispersed by strong tides and deep water. “They’re only pollutants when they’re really concentrated,” says Sims.

Ocean Era received a permit from the Environmental Protection Agency last year, but the Waterkeeper and other organizations are fighting that decision, which is currently being reviewed. To build the fish farm, Ocean Era must also receive approval for its construction plans from the Army Corps of Engineers. A decision on that permit is expected any day. The Waterkeeper and other groups pledge to combat that permit, as well, if it is issued.

Gentrup and Bloom warn that Velella Epsilon represents just the tip of the iceberg for aquaculture in the Gulf. “This would open up a pipeline for the development of many of these fish farms,” says Bloom.

Indeed, if Velella Epsilon is successful, Ocean Era plans to grow its Gulf operation exponentially. Sims says the company will evaluate how well the kampachi grow in the Gulf and whether Ocean Era can win over the commercial and recreational fishing industries, which are often skeptical of aquaculture because of the increased competition aquaculture can bring.

If the results are positive, you can expect to see another farm with as many as 2 million fish in the Gulf. According to Sims, that size is an industry standard. “There are certain economies of scale,” he says. “Two thousand tons a year is the minimum for any aquaculture operation.”

Other companies may also join Ocean Era. “By blazing this trail through the permitting process, we want to build an industry,” says Sims. “We don’t want to just be one farm out there.”