The Genius and Daring of the Late Clifford Irving

My desire to become a writer crystallized during the Clifford Irving/Howard Hughes scandal of the early 1970s. It was an inspiration to me. Imagine—being such a good writer you can pull off a phony autobiography of a public figure, and pull it off so well that—at first, anyway—everybody believed it. Then to have the whole thing collapse and you end up in prison. I knew instinctively that if I was going to be a writer, that’s the kind I would be.

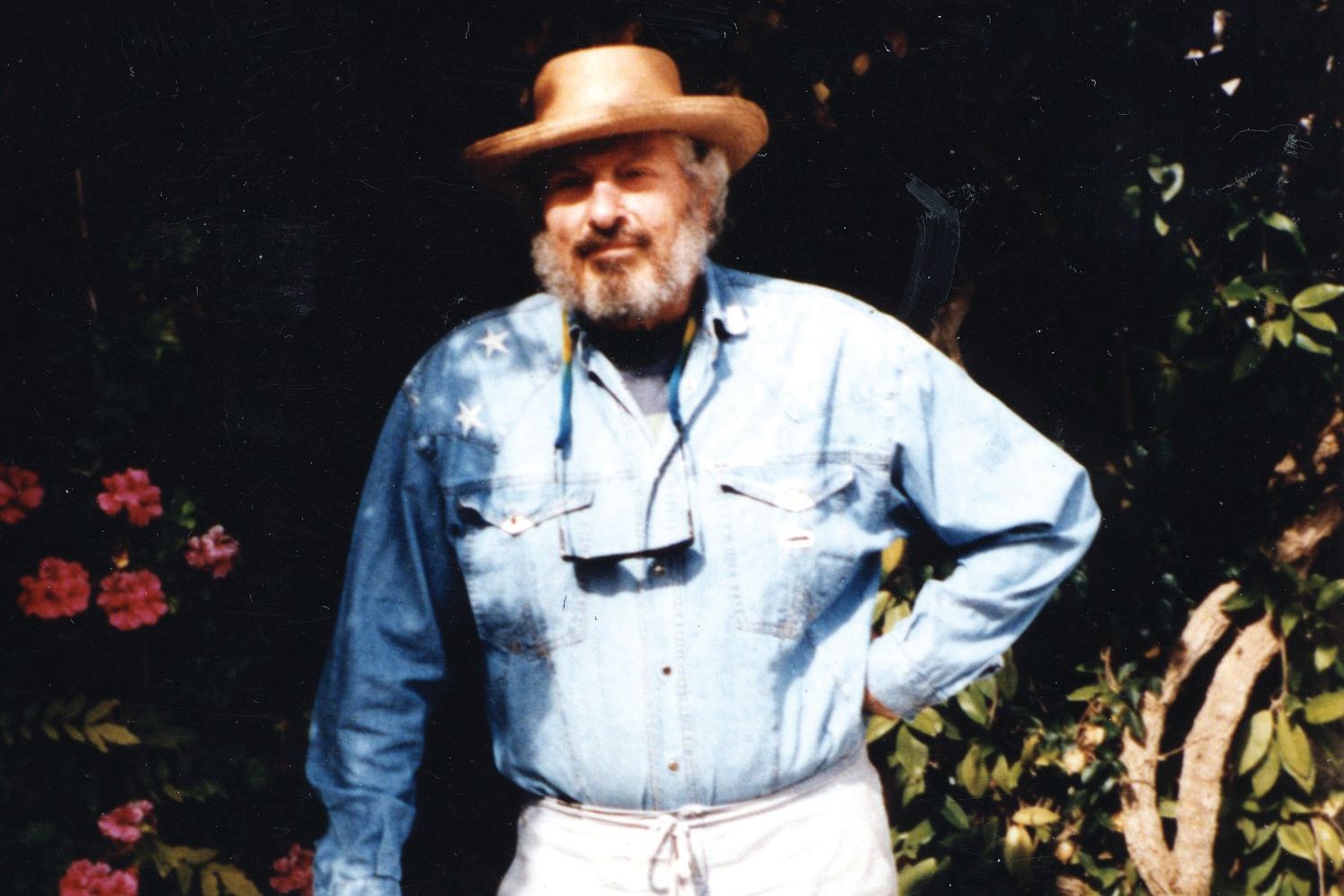

So one of the great pleasures of the past five years or so was getting to know my idol Clifford Irving. We had lunch regularly, usually at Gecko’s on Hillview, as Cliff much preferred informal places and would invariably show up in shorts and sandals. He was an enormous man, 6 feet, 4 inches, I believe, lanky and angular. He spoke softly and was hard of hearing. It didn’t matter. A rapport developed and soon we were exchanging things we were working on, to get each other’s input.

But frankly, what I wanted to know was the story of his life. And slowly, over a period of time and in bits and pieces, I finally got to hear it.

I certainly can’t tell you the timeline. When Cliff passed away just before Christmas, he was 87 and had been married six times, plus having three girlfriend/companions that he didn’t marry. He’d lived all over the world, worked with Orson Welles, appeared on the cover of Time, won a monkey in a poker game, served 17 months in prison and been played by Richard Gere in a movie.

So there was a lot to tell.

Cliff was a mid-level writer of both fiction and nonfiction back in the late 1960s, living on the Spanish island of Ibiza, when he befriended a notorious Hungarian art forger named Elmyr de Hory. De Hory had an uncanny ability to mimic the style of certain modern painters, such as Modigliani and Picasso, and over the years had sold hundreds of fakes to prominent collectors and museums who were delighted to get these “masterpieces” at greatly reduced prices.

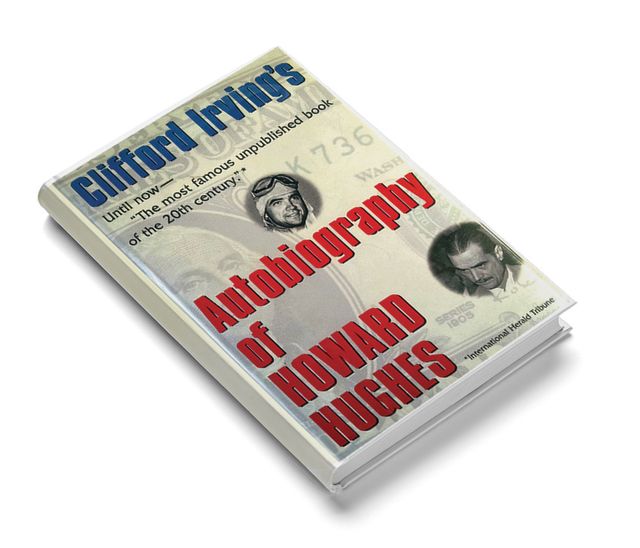

Cliff told De Hory’s story in a book called Fake! It was a big success and, I feel certain, planted the seed for Cliff’s next project. Knowing that billionaire Howard Hughes was a complete recluse, holed up in a hotel in the Bahamas and never allowing the outside world to intrude into his hermetic life, Cliff decided he would write his “autobiography.” He would say that Hughes had contacted him, expressed admiration for Fake! and wanted him to ghostwrite the story of his life. Thus began the hoax.

For those too young to remember, it’s hard to overstate the sensation the hoax caused. It was one of the great media circuses of the 1970s. Cliff got almost a million dollars in advance and the “autobiography” itself was declared genuine by all the experts. Even the handwriting (Cliff got some help from an artist friend on Ibiza) was judged to be Hughes’s. Cliff even passed a lie detector test.

And he was having the time of his life. Challenges of nerve and invention were thrown at him from all sides and he met them all. He totally won over Mike Wallace during an interview on 60 Minutes. He got so good at deception that he got a little reckless. A trip to Mexico for a secret meeting with Hughes was actually a tryst with his mistress, the glamorous Danish baroness Nina van Pallandt, who sort of became the Kato Kaelin of the case.

Finally Hughes was driven to do what he hadn’t done in decades—talk to the press. In a 1972 conference phone call with seven reporters, he proclaimed that Cliff was a fraud and that he had never met him, never talked to him, never authorized anything. The whole scheme suddenly fell apart and Cliff and his then-wife Edith were arrested on multiple charges.

Cliff, who was so good at portraying human nature in his writing, seriously misjudged it this time. He was suddenly a “con man,” pure and simple. “If we got caught we always thought we’d just apologize and give the money back,” he said. But the duped parties didn’t see it as a joke. Cliff’s adventure was equated with crime, and it sort of ruined his life.

There was always a stigma that followed him after that. Self-righteous people turned on him. When he spent the summer before he went to prison in Sarasota, MacKinlay Kantor, then the dean of the Sarasota writing community, refused to meet him on the grounds that he had disrespected the publishing business. I remember Cliff telling me once about an expensive painting he owned that he wanted to get rid of. “Why don’t you just sell it?” I asked. He sighed. “Who’d buy a painting from me?’”

Cliff’s last wife, Julie, had, if not a sense of humor, at least a sense of irony about their situation. She wanted her email address to be mrs.irving6. (Cliff talked her out of it.) They met in a ski line in Aspen years ago, when she was a young Australian divorcee traveling the world, looking for an adventure. Cliff turned out to be her adventure. He led her to a nomadic life in glamorous places like Aspen and San Miguel Allende and later to a life of quiet contentment as a husband who grew mellower as he grew older. That’s a good thing, as he could be selfish and difficult. His ex-wives and three sons were used to him ignoring things that cannot be ignored. “Just deal with it!” he would tell them.

By the time Cliff and Julie settled full time in Sarasota, their lives had become pleasant and simple. They lived in a nice but hardly elaborate midcentury house on Phillippi Creek, and Cliff wrote every day. He taught himself how to sell his books online and became very successful at it. A whole new generation of readers who had never heard of the hoax discovered him and his fast-paced legal thrillers. His voracious curiosity about the world never diminished.

But slowly, his gregarious nature changed to something much more reclusive. He spent his days swimming in the pool (he was big on exercise) and reading, writing and playing chess (which he learned from the black guys in prison) on one of those websites where they hook you up with an anonymous partner. His favorite was an 11-year-old girl who beat him regularly.

During our lunches we both—being a couple of geezers—loved to talk about our health. His was remarkably good—until one day last November. Julie was in Australia visiting relatives and he wasn’t feeling well. The doctor said it was a hiatal hernia, and they were trying to decide on a course of treatment.

Julie got back the next week and realized something was seriously wrong. Another doctor’s visit revealed the real problem. Cliff had pancreatic cancer.

We had discussed death before. Cliff’s attitude was to take charge and turn it into something special. The ideal way to go, he said, would be to climb to the top of his favorite mountain in Aspen and lie down in the snow with a bottle of scotch and just fall asleep.

Within days of his diagnosis, Cliff was placed in hospice. He was comfortable and the family was there. “I’ve had an amazing life,” he told them. “But I’m ready.” It’s like he was lying in the snow on that mountain.

One afternoon just before the end, he had a confidential talk with the doctor. “Can you help me out?” he asked. “Can you give me something?”

“I’m sorry,” the doctor said. “We have to let nature take its course.”

“Oh, come on, doc,” he said, and for one last time turned on that famous charm. “I won’t tell anybody.”

Cliff is gone and along with him one of the most colorful, disruptive and enigmatic figures in American literature. He pulled off something only a master could. Not even Nabokov or Henry James could come up with anything so audacious and execute it so brilliantly. That’s what the world still doesn’t quite see—the art that went into the hoax. Cliff paid a price for his genius, but at least he ended up on the mountain. He accomplished something very rare for a writer. He became a part of history.