The Heist That Rocked Sarasota's Art World

The Sarasota artist colony of painters and writers who flourished here in the ’50s and ’60s is long gone, and with it a remarkable group of men and women. These people set the tone of the town and did it so well that, today, the arts remain as central to Sarasota’s identity as its beaches. There may be one or two of these individuals left, but, as a group, they are fading into history.

Some ended up world famous. Syd Solomon’s paintings are in most major museums, John D. MacDonald is credited with creating modern crime fiction and MacKinlay Kantor’s story The Best Years of Our Lives is firmly embedded in our national psyche due to the classic movie based on it. Burl Ives, meanwhile, remains integral to the Christmas season thanks to his “Have a Holly Jolly Christmas.” And Julio De Diego, one of the more interesting of the painters, married Gypsy Rose Lee, the most famous stripper in the world, and spent the next several years managing her burlesque show.

And then there was Ben Stahl. In his heyday, he was one of the most famous Sarasota artists of all. One of the country’s top illustrators, he was so good he could almost cross the line into fine art. He had an entrepreneurial streak a mile wide and was always trying something new and potentially profitable. He set out to write a novel and it became a bestseller and then a Disney movie. He co-founded the Famous Artists School with his pal Norman Rockwell. He even opened his own museum, the Museum of the Cross, in which he exhibited a series of his own paintings depicting the stations of the cross—the final hours of Jesus’ life.

For three years in the late ’60s, the museum was one of the town’s major tourist attractions. Then, on April 16, 1969, it became something else—the scene of Sarasota’s most baffling mystery.

Inside the Museum of the Cross

When Ben and Ella Stahl moved to Sarasota in 1953, the town had already acquired an arty reputation. The stage had been set early. Bertha Palmer had brought her favorite Monet down to hang over her fireplace at the Oaks and John Ringling’s art collection, both eccentric and eclectic, opened to the public in 1936.

Artists like Ben moved here for the simplest of reasons. It was a great place to work. The weather was beautiful, as were the colors of the Gulf and the tropical vegetation. Life here was also relatively cheap, there were many kindred spirits and there was even the circus to liven things up. People still talk about the social life back in those days, and some of the tales get quite racy. The alpha male artist or writer with an inflated ego and a drinking problem—we had our share.

Ben was not like that. I knew him during the last year of his life, and found him charming and great company, yet always a little reserved. Unlike most of the artists, he didn’t talk much about himself. He was the sort of person who, when he left the room, everybody started talking about him.

There was a lot to talk about. He had been one of the top illustrators in the country at a time when illustrators were in high demand. It was the golden age of magazines, and it was men (they were invariably men) like Ben who drew the illustrations that accompanied the articles and the ads. Ben illustrated more than 750 stories and covers for the Saturday Evening Post, the gold standard of 1950s mainstream media.

And it wasn’t just the Post. His work also appeared in Vogue, Ladies’ Home Journal, Collier’s and more. He even drew Coca-Cola ads. He was the guy who got the plum assignments. Esquire hired him to do 12 portraits of beautiful young girls, each one typical of her European country.

He had his own style, or rather a style that pulled from the work of many famous artists—a little Renoir, a little Degas, a little Picasso and, when he was getting serious, a little El Greco. But he had a happy view of life. His favorite subject was a voluptuous nude, blissfully plump and smiling. I happen to know, because I own one. I won it from him in a poker game.

Of course, the Saturday Evening Post would only publish so many nudes, so he had other specialties. He had an affinity for religious paintings, very dramatic in color and composition, with figures posed to suggest the Old Masters. But he could please anybody. Even the Air Force, which hired him to do a series of paintings for their academy in Colorado Springs. His work even hangs in the Pentagon.

Ben became a leader in Sarasota’s artist colony, perhaps the most vocal. “He was a domineering presence in the community,” wrote Marcia Corbino, “a catalyst who was stimulated by obstacles.” He was always advocating for increased funding for the arts and getting into spats with politicians. He raised a terrible ruckus when members of the Florida Legislature refused to pay him for a portrait they commissioned of Gov. Claude Kirk.

His talent was not limited to painting. After an argument with John D. MacDonald about which was more difficult, writing or painting, he set out to write a novel. How hard could it be? The result was Blackbeard’s Ghost.

And, since he happened to have an appointment in California, he decided that while there he should talk to Walt Disney about his book, as yet unpublished. Walt was intrigued by this person from Florida who somehow managed to get his phone number and invited him to lunch at his studio. Three days later, Walt bought the movie rights and William Morrow called, looking to publish the novel. The book won prizes and the movie was a success. Everybody was pleased, except Ben, who told people, “The movie was horrible.”

The reason for Ben’s trip to Los Angeles was just as unlikely and just as thrilling. He was to paint a nude portrait of Ursula Andress—the original Bond girl—that would hang over the bar in a movie called 4 for Texas, also starring Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Anita Ekberg. Stahl’s work was often used for movie publicity. He did a series of paintings to promote Ben-Hur in 1959.

The Stahls had four children, whom many old timers around town remember from high school. The family was well known for their lavish home. It was designed by Sarasota School architect Victor Lundy and is credited with being the first of the Siesta Key showplaces. Ben did his best to adjust to modernism, but all those glass walls bothered him. There was nowhere to hang paintings. “It took us 10 years to rework it and make it livable,” he complained.

But life was glamourous. There was always an exciting, lucrative project to work on, many of them abroad. Neighbor MacKinlay Kantor suggested the Stahls spend some time in Torremolinos, Spain, where they hung out with Hemingway and Jacques Cousteau. During a stay in Hong Kong, they discovered a 4-year-old girl who played the piano like a pro, only cuter. Her name was Ginny Tui. They arranged for her to come to the States, where she appeared on Ed Sullivan, created a sensation and then went on to a successful acting career that included appearing in Girls! Girls! Girls! with Elvis Presley.

One of Ben Stahl’s Museum of the Cross paintings that was stolen in 1969.

Ben had been somewhat of a child prodigy himself. His grandmother saw his talent early and took him to museums. But he had no formal education and never went to art school. At 16, he began working at a commercial art studio. That same year, he placed a watercolor in a prestigious exhibit.

To Ben, the role of the artist was not that of a tortured soul but rather an explainer, a guide. The artist was there to entertain, delight and inspire. It was this attitude that made him such a great teacher. Practically all the visual artists in the colony taught. Sarasota in the ’50s was clogged with art schools. There was Syd Solomon’s school, the Hartman school, Hilton Leech’s school, Jerry Farnsworth and Helen Sawyer’s school—they were everywhere.

But Ben thought much bigger than Sarasota. He became a founding member of the Famous Artists School, a mail-order art school that became a midcentury phenomenon. To sign up, you took a talent test (which no one ever seemed to fail) and then a salesman would appear at your home and sell you the course. It cost $300, a hefty sum in the 1950s. You were mailed lessons, which you completed and mailed back. These were critiqued by staff (certainly not by the famous artists). The school grabbed the imagination of the country and, at its peak, claimed 40,000 students, including Dinah Shore, who appeared in one of the ads in a particularly flattering portrait.

The Famous Artists created the curriculum and pocketed most of the tuition. Still, it seems to have been a legitimate, well-thought-out course. The textbooks are still around and are well regarded even today. Ben also appeared on the TV show The Joy of Painting, offering lessons with his good friend Bob Ross.

With success came expansion, and Famous Artists added other professions—writers, cartoonists, photographers, even accountants. But a sensational article by Jessica Mitford brought the whole thing down. She exposed the hard sell, the contracts you had to sign and the legal actions against people who tried to quit, not to mention the staff of drunken hacks who did the real work. While these claims were leveled specifically against the writers’ branch of the school, it burst the bubble for everyone and, by 1972, Famous Artists was in bankruptcy court, the victim of bad press and overexpansion.

But, well before then, Ben had moved on to a new adventure. He was about to paint his masterpiece.

Ben and Ella Stahl (left) with two associates, planning construction of the Museum of the Cross’ second location.

In 1954, the Catholic Press put out a new special “papal” edition of the Bible. To illustrate the crucifixion, the publisher hired Ben to create 14 paintings that would show the stations of the cross, the iconic final moments of Jesus’ life as he carried his cross to Calvary.

Ben had illustrated books before. It was, in fact, one of his specialties. His work included special editions of Little Women, Gone With the Wind and even Madame Bovary. But this was different. It was not just a book. It was the book.

Ben and Ella went to Jerusalem for three months to study the locations and immerse themselves in the atmosphere of Jesus’ world. Back home, as the project came together in Ben’s studio, it turned out to be a job like no other. As he worked for the next two years, he found that the spiritual dimensions of the paintings were affecting him. His son David recalls how his father could actually paint the face of Christ in as few as 30 or 40 strokes. “He was really amazed by that,” David says.

The new Catholic Bible became a great success, and people began to ask about the paintings. Where were they? Could they be viewed and experienced firsthand?

This set the Stahls to thinking. This could be Ben’s ultimate project—a museum of his own work. Of course, the originals were too small to have the necessary impact, so Ben went back to work, painting new versions, each one 6 feet by 9 feet, and adding a 15th painting to complete the narrative. To exhibit them, the Stahls decided on a famous local building, designed by Victor Lundy. It was on the Trail, just to the north of Sarasota High School. It was circular, with glass walls, and had been home to Galloway’s Furniture Store. Ben and Ella purchased it, did some renovations and in November 1966, the Museum of the Cross opened.

It was an immediate success. Critics raved and the crowds showed up. It was not unusual for the museum to receive 1,500 visitors each week. Religious leaders like Norman Vincent Peale endorsed it enthusiastically and it soon became one of the town’s leading attractions.

The building, though, was somewhat of a problem, so Ben hired an architect from Bradenton named Gene Willis and built a new space to his specifications. That structure was located farther south on the Trail and was oval in shape, with an inner gallery that contained other exhibits: several other religious paintings not by Ben and a collection of artifacts, mostly crucifixes, that the Stahls had collected during their travels.

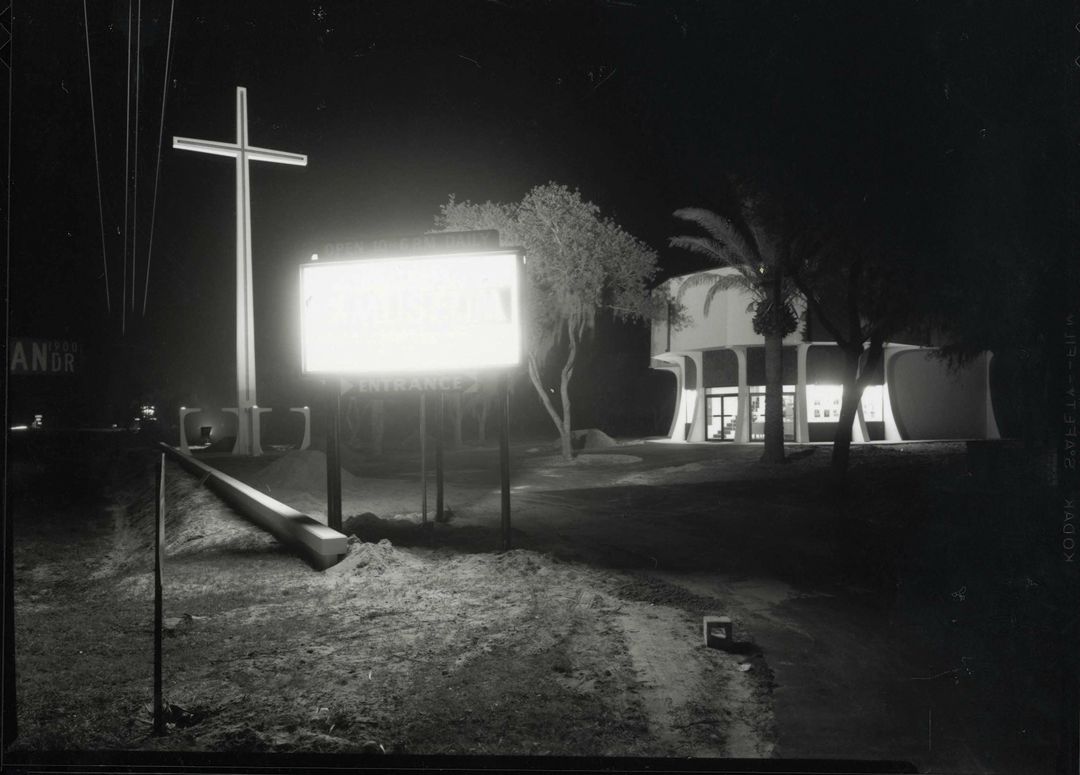

Sarasota artist Virginia Hoffman remembers visiting the museum when she was 12 years old, with her Sunday school class. “I was impressed,” she says. “It was a real museum, specially lighted, very subdued. I can still remember the velvet draperies.” Outside was a garden based on the garden at Gethsemane, where Jesus was arrested before being crucified. To announce the museum to cars cruising by on Highway 41, a 60-foot-high white and gold cross was constructed.

The paintings themselves are tricky to classify. They hover the line between art and illustration. They look like they are illustrating a story, which of course they are. To contemporary eyes, they lack the depth of great art, but the technique is remarkable and the total effect very dramatic. Many patrons left visibly moved, some in tears.

And then, all of a sudden, the paintings vanished.

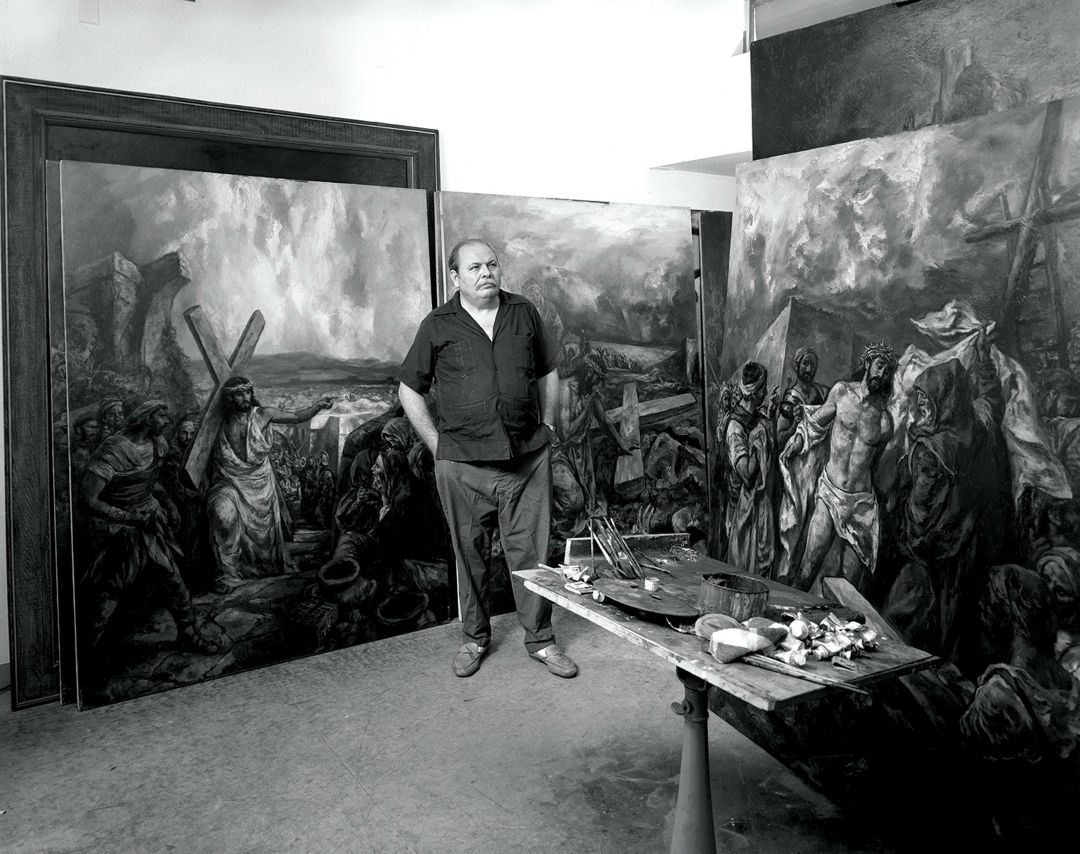

Ben in his studio, with the stations of the cross paintings.

Ben got the call early on the morning of April 16, 1969. As unbelievable as it sounded, someone had broken into the museum late at night through a fire door and had stolen all 15 of Ben’s paintings. Each of the works had been carefully taken out of its frame and then each staple holding it to its inner wooden frame had been pried off before it was presumably rolled up and carted away. Usually, in an art theft, the painting is simply cut from its frame with a knife.

Whoever stole Ben’s paintings had taken their time in order to do minimal damage to the works.

The police could find no clues. No witnesses. No fingerprints. There was no alarm, no night guard. Ben was trying to cut back on expenses. He had just bought an expensive new sound system and was more worried about that being stolen than the paintings. Some neighbors said they saw a white van in the parking lot, but that was it. Ben ruefully recalled a remark he had made publicly about a month before the crime: Someone had offered him $1 million for the complete set.

Who would steal religious paintings from an atmosphere that to many (including Ben) was almost as holy as a church? “I couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t understand why the paintings should be insured,” his daughter Gail later said.

Over the years, the robbery has earned a reputation in true crime circles as a particularly bizarre case, as unlikely and inexplicable an enigma as the Malaysian airliner that disappeared in 2014. Every theory sounds crazy. Every possible explanation is full of holes and sounds preposterous.

One story says that the paintings were kidnapped and held for ransom, with a skittish priest acting as an intermediary. Sightings of the works have been reported all over the world, in places as far flung as a storeroom in an art museum in Fort Lauderdale and a flea market in Turkey. Latin America comes up over and over again in theories. Ben himself came to believe that they were in the possession of a wealthy Brazilian or Mexican who kept them in a remote location and derived spiritual satisfaction from gazing at them. The most bizarre theory of all connects the crime to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., which occurred almost exactly a year before. (Yes, I wish I had more details on this one, too.)

Ben was devastated by the crime and, although he never said so, his feelings must have been hurt by the whispers that it was somehow an inside job or an insurance scam. But the paintings were not insured, and the Stahls took a terrible financial hit. The bank repossessed their home, which was heavily mortgaged to pay for the museum. “The truth is the robbery ruined us financially,” he said in 1981. “It took me for everything, probably a couple of million bucks.”

Still feeling the shock, Ben and Ella later moved to San Miguel de Allende in Mexico, where an artist colony very much like the one in Sarasota was flourishing. There, Ben got his old spirit back and was soon running the place. By then, he was mostly painting for his own pleasure and doing his best work. When Ben became ill, the Stahls moved back to Sarasota and Ben died here in 1987, still not knowing what happened to his masterpiece.

The search for the truth then fell on Ben’s kids, particularly David, who became a photographer and painter of some acclaim. He feels the investigation was bungled by both the local police and the FBI and cites a list of irregularities, including files supposedly lost in floods and fires at the police department. The crime was featured on the TV show Unsolved Mysteries in 1992, but the episode failed to generate any new leads. The Sarasota Police Department reopened the case in 2013, but, again, nothing new turned up. The case is so old that the statute of limitations has run its course, and even if the truth does come out, it’s unclear if anyone would be held accountable.

And still: nothing.

The exterior of the Museum of the Cross

The Museum of the Cross is still there. You can find it at the entrance to Coral Cove on the South Trail. It now houses a dermatology practice, and the interior has been completely reconfigured. But stroll around the parking lot. The distinct oval shape of the building is still apparent and, if you look carefully, you’ll see the fire door the thieves broke into. It’s easy to imagine a white van parked nearby, ready and waiting.

The museum is one of the few relics left behind by the artist colony. Ben and Ella’s house was torn down, as were MacKinlay Kantor’s and Syd Solomon’s. Their old hangouts, the bars and restaurants that made downtown so lively back in those days—they’re gone too.

Luckily, the art lives on. Paintings and drawings by Ben are easily found online. The prices vary, and I was a little saddened that he didn’t bring larger sums—particularly because I own one.

No, wait, I own two. My other Ben Stahl was given to me by Joan Griffith shortly before her death. (Griffith was the daughter of Helen Griffith, a longtime society columnist for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune and the social media arbiter of her day.) The item is a dirty tablecloth. It had been, Joan said, one of her mother’s favorite possessions. When I took it home and unfolded it, I saw why.

Ben had drawn all over it. It’s even dated: Oct. 7, 1968, at the very height of his museum’s success. It’s the happy souvenir of a tipsy night at the famous Plaza Restaurant, the place to go to back in those days. You can see a portrait of a man who looks just like Syd Solomon and another of a bespectacled character identified as “Roman.” You’ll also find various jottings, references to long-forgotten jokes and gossip. But the star of the tablecloth is clearly Helen. There are several drawings of her, one of her grinning madly and one of her naked and about to sit down on a block of ice.

That was Ben Stahl—a little bit sacred and a little bit profane, always the best of company and always the center of the action. Though he’s been dead for 36 years, he still seems to exist in some sort of limbo, a piece of a mystery that has yet to be solved. Will it ever? I hope so. I’d love for Ben to see one more moment in the spotlight.