The End of the Run for Con Artist James Hogue

The con man The New Yorker famously dubbed “The Runner” in 2001 shuffled down the hallway of Aspen’s Pitkin County Courthouse, his legs chained, his hands cuffed.

March 20, 2017, was the first time in more than six weeks that James Arthur Hogue, then 57, had seen the sun, as the Aspen jail—usually short-term housing for drunks and petty thieves—has no outdoor exercise yard. His pallor was sheet-white pale.

In less than 15 minutes, he would be sentenced for his latest spate of criminal transgressions: felony possession of burglary tools and the theft of items (from ski gear to construction materials and tools to designer clothing) valued between $2,000 and $5,000, and obstructing a peace officer, a misdemeanor.

Such workaday offenses seemed far removed from Hogue’s criminal glory days in the mid-’80s, when he gained national notoriety for a pair of high-profile impersonations. In September 1985, a month before his 26th birthday, he enrolled in Palo Alto High School in California and passed himself off as a 16-year-old endurance runner gunning for a collegiate scholarship. A few years later, after having invented a convoluted backstory, he fraudulently enrolled in Princeton University and ran track for the Tigers.

Both times he was caught, and his hijinks yielded a tsunami of magazine and newspaper articles, as well as a book and an HBO documentary. Hogue became the last thing a serial impersonator wants to be: well known, a bona fide public figure.

As he now limped by on his way to his sentencing hearing, dressed head-to-toe in bright orange, he turned his head slightly and said to me, “Hi, John.”

X

I had started visiting Hogue in jail last winter, after having heard about his most-recent arrest, which occurred on November 3, 2016, outside the Pitkin County Library in Aspen. Until his world once again began unraveling two months prior, he had been living in an unlikely abode: an upscale shack—an oxymoron if ever there was one—that he had constructed on the side of Aspen Mountain, in the middle of the 13-acre Barbee Open Space parcel, located a stone’s throw from some of the priciest slopeside real estate in the country.

According to an Aspen Open Space ranger who prefers to remain anonymous, in mid-September 2016, Hogue aroused the suspicion of Aspen Skiing Company (SkiCo) employees after a number of tools had gone missing from a worksite in the vicinity of Lift 1A. Having observed Hogue—whom their boss later described to police as a “transient”—frequenting the area, they eventually followed him through the thick brush and found his shack. Authorities were alerted.

The next day, the ranger approached the abode with two Aspen police officers, and the group politely knocked on the front door.

“The guy’s head popped out of a back window,” the ranger told me when, in late March, he showed me where Hogue’s long-gone domicile had been located. “He didn’t say anything, but he lowered himself down a ladder attached to the back and ran off into the woods.”

The threesome peered through the window and saw that the cabin was far more civilized than most of the average squatter camps rangers find scattered throughout the woods surrounding Aspen, where hyper-inflated housing costs often force lower-rung workers to seek alternative accommodations.

Aspen police officer Ian MacAyeal described it this way in an e-mail he sent to the entire department on September 16, 2016: “Illegal campsite (more like Aspen employee housing) fully enclosed shack on foundation with bed, shelves, cook stove and satellite radio.... Tons of stuff up there. Looks like this guy’s been there for years.”

In addition to personal items, Hogue’s makeshift home seemed to be as well stocked with high-end ski gear and apparel as a downtown Aspen boutique. “When we returned the next day to begin the process of demolishing the shack, the place had been completely cleaned out,” the ranger recalled, adding that it took Open Space employees almost a week to raze the shack.

It was a perplexing place to build a residence. The side slope was so steep it was hard to stand without slipping. Though Hogue had sacrificed a few dozen small trees to prepare his building site, it was still a tiny footprint. His design aesthetic was clearly centered around concealment.

“He obviously knew what he was doing,” the ranger said. “He strapped braces to the downhill trees to make a level platform. He used only screws. No nails. He painted the sides camouflage green. Even in the winter, the shack was invisible unless you were right on it.”

On November 1, not long after the shack was removed, a supervisor from SkiCo’s Trails Maintenance Division called Aspen Police to report that the man who had built it had returned to the area, and had fled after two of his employees confronted him about a cordless drill and an extra battery that had disappeared from their construction site. According to the police report, the employees discovered that the man had been “digging a large hole in the ground and lining it with large pieces of plywood that appeared to be from the previous building site.”

There, they found not only the stolen SkiCo drill and battery, but also several other company tools that had gone missing. Soon after the incident, the employees observed the man carrying several large duffel bags down the hill to a SkiCo employee parking lot, where he loaded the bags into a green 2005 Nissan Xterra. When Detective Jeffrey Fain ran the license plate through a law-enforcement database he discovered that the vehicle was registered to James Arthur Hogue, a convicted felon who was wanted on outstanding arrest warrants in Boulder County for counterfeiting and larceny. Fain asked the local papers to alert the public and publish a photograph of Hogue.

The next day, an employee of the Pitkin County Library, having seen Hogue’s photo in the newspaper, called the Aspen PD. When Officer Dan Davis confronted Hogue near the library’s public computers, he identified himself as David Bee, the latest of many aliases.

After he was taken into custody, with Hogue’s permission, Aspen police searched that green Xterra. In it, they recovered and processed a list of suspected stolen goods that covered nearly three single-spaced pages of the police report, from items as mundane as several unused water bottles to as high-end as a Ralph Lauren coat worth almost a grand. Much of the clothing, as well as various sets of skis and snowboards, still had the price tags attached.

Police also found a handwritten register that suggested Hogue had been running an online business, selling property presumed to be stolen. And they found nearly $17,000 in cash, mostly in 100-dollar bills.

Before meeting with Hogue, I had read the piece in The New Yorker, as well as a half dozen other newspaper and magazine articles. I had watched the documentary Con Man several times. Almost every single story dedicated to Hogue spoke of his impressive intellect. He has been described as a genius gone wrong, a man who reads books on quantum field theory like other people read Tom Clancy novels.

If this guy is so damned smart, I wondered, why on earth would he remain so close to the scene of a felonious crime? Once his original shack was discovered, he could have—should have—fired up that Xterra and fled the Roaring Fork Valley forever, or at least till things cooled down. How could someone so smart be so stupid as to start building a new shack less than 200 feet from the old one? And to steal tools from the very same people who had just confronted him two weeks prior?

I wanted to find out what makes this guy tick.

X

I had been told by several people that, since his spate of notoriety more than 20 years ago, Hogue had ascribed to a personal media blackout. He didn’t talk to many regular people, but he flat-out refused to talk to reporters. The chance of Hogue agreeing to meet with me seemed slim enough that I engaged in a last-resort tactic right off the bat. I handwrote him a straightforward missive in which I explained that I was on assignment to write a magazine article about him—with the implication that I would pen the piece with or without his cooperation. I placed the note inside a book I wrote several years ago, a book that tells of travels through some seriously wild places, the kinds of places I knew from reading about his various exploits that Hogue himself likes to visit.

The package, which I dropped off at the Pitkin County Jail on a snowy February morning, was, admittedly, part bribe, part blackmail.

Surprisingly, a week later, I got a call from Hogue.

Though he sounded hesitant, he consented to meet but stated, “I’m not really interested in being interviewed.” Our conversations would be limited to small talk.

Interaction between visitors and inmates at the jail takes place via telephone, with a thick pane of glass serving as a barrier to even rudimentary intimacy. It was an awkward way to introduce oneself to an obviously skeptical subject.

Hogue is of medium build, though he looks smaller. Even as he approaches his sixth decade, he retains a touch of the boyish countenance that allowed him to once play the role of a high school student 10 years his junior. But his sandy-brown hairline is receding. The runner is starting to nurture a paunch. He has deep wrinkles on the back of his neck. He is clean shaven and meticulously groomed. He looks more like an accountant than a transient.

I began by thanking Hogue for agreeing to let me visit. Then I asked why he had decided to do so.

“It gets pretty boring in here,” he responded, making little eye contact, a trait commonly noted in the many articles penned about him.

I asked how he spends his days.

“I read a lot and watch TV,” he stated. “There’s a workout room, and there are yoga classes. We play cards.”

Grasping at conversational straws, while resisting the overwhelming temptation to slide into Q&A reporter mode, I asked if he was a practitioner of yoga.

“Not until I got here,” he said, adding that once he left the jail, he and yoga would likely part ways.

When our allotted time drew to a close, I asked Hogue if he would allow me to visit him again. After a pause, he said, drily, “OK.”

X

On my second visit, he loosened up ever so slightly. He said he first visited the Rocky Mountains as a child. His family used to vacation in Wyoming’s Medicine Bow Mountains, where his grandparents owned a vacation cabin. Returning to his native table-flat Kansas City, Kansas, Hogue dreamed of one day moving full time to the land of vertical topography. “I wanted to ski,” he said, before looking away and sighing, which I came to learn meant that I should back off on my interrogation.

Background research told me that, having distinguished himself as a distance runner at Washington High School, Hogue earned a full-ride track scholarship at the University of Wyoming in 1985, but dropped out in his sophomore year when he realized he was no match for the Kenyan runners on the team.

That led to his first con: passing himself off as a teenage track star at Palo Alto High School. Once that scam was exposed, Hogue seems to have fled to Colorado, where he said he briefly worked on a dude ranch in Meredith.

Eventually, famed trainer Jim Davis hired Hogue as a coach at his Vail Cross-Training Camp, where he worked alongside such notable endurance athletes as Frank Shorter and Scott Molina. That experience circuitously resulted in the first of Hogue’s many felony-level arrests.

Davis says he first met Hogue in 1986 in Vail. “It was still ski season,” Davis recalls. “We ran to the top of Vail Mountain, all the way down Eagles Nest to the gondola. Money was involved. I think it was $300 for first place. The top mountain runners in Colorado were there. Hogue took second, behind [professional triathlete] Andreas Boesel. He was very impressive. Dude could run. I decided to hire him the following summer to work as an instructor at my camp, which I ran for eight years.”

Davis says Hogue arrived with an autobiography that was superficially believable—especially in a part of the country where it’s not uncommon for people to modify or erase their past.

“He worked for me two summers,” Davis says. “He passed himself off as a professor of bioengineering at Stanford. The camps only ran for about a week. James helped with the running and the bicycling. He would show up a bit before the camps started and hang out for a week or two afterwards. He couch-surfed. The staff would spend evenings sitting on the deck drinking margaritas. He fit in, but not quite. He was always a bit standoffish, but a lot of distance runners are like that. He contributed. But when he left, he just disappeared. It was pretty much the same thing the second summer.”

Davis offered Hogue the chance to return to the Cross-Training Camp a third summer, but, by then, Hogue’s life had begun a downward spiral that has not, 30 years later, fully cratered out.

“I got a call from a runner friend in Colorado Springs telling me that, whatever James says, don’t believe him, it’s not true,” Davis says. “At the time, I was an avid Runners World magazine reader, but, somehow, I had missed the story about James and his situation at Palo Alto High School. My Colorado Springs friend mentioned that article. After that, I called Stanford, and they, of course, had never heard of James Hogue, as a professor or a student. What’s weird is that he didn’t have to lie to us. We hired him because he was good at running.”

The backlash from Hogue’s time in Vail did not end with the unmasking of his false professorship.

It was through Davis that Hogue met Dave Tesch, owner of the Tesch Bicycle Company in San Marcos, California. After leaving Vail the second summer, Hogue went to San Marcos and began hanging out at Tesch’s shop, still claiming to be a Stanford professor. In October 1987, the shop was robbed of $20,000 in bike frames, parts, and tools.

As detailed in The New Yorker article, the next spring a visitor to Tesch’s shop recounted a curious incident. A friend had been at a party in St. George, Utah, where a man named Jim Hogue had shown him a metric dial caliper engraved with Tesch’s name.

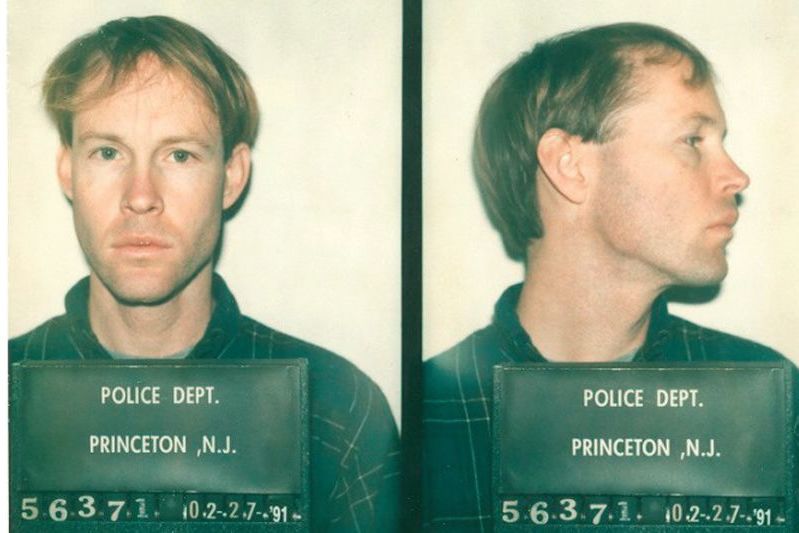

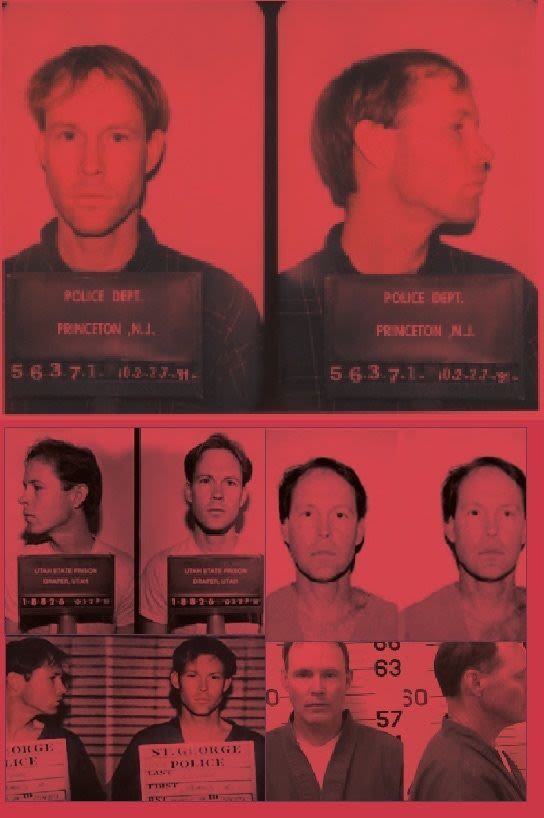

Upon hearing the news, Tesch drove to St. George, where he met with a local detective who obtained a search warrant for a storage locker rented by Hogue. Tesch identified the stolen bike parts. After his arrest, Hogue pled guilty and was sentenced to one to five years in prison; he was paroled in less than a year.

Hogue’s Gallery of mug shots throughout the years.

X

On March 20, 2017, Hogue was first on the sentencing docket of Pitkin County District Court Judge Christopher Seldin. Since Hogue had already pled guilty in early February, all that was left before Seldin articulated his fate were sentencing recommendations from the attorneys. In one corner was Molly Owens, Hogue’s court-appointed public defender. In the other corner was Deputy District Attorney Sarah Oszczakiewicz.

James Hogue before sentencing.

Image: Craig Turpin

Owens, who did not respond to any of my numerous interview requests, argued that Hogue was at least partially a victim of his public persona, who in the media “is portrayed often as someone who is sneaky, as someone who is a folk hero of sorts ... The man I know is simple and humble, and has recently lived a life of isolation.” She opined that Hogue was not a danger to the community, that he had constructed his shack out of fiscal desperation. And she introduced a letter penned by longtime Hogue acquaintance Peter Hessler, a successful author and staff writer at The New Yorker who ran track with Hogue at Princeton.

“In my conversations with Hogue, he has described his thefts as a kind of compulsion,” Hessler wrote. “I recommend that any new sentence involve some form of counseling. Hogue is in many ways a very functioning individual, with a range of skills both intellectual and practical.... There should be some way that such a person can become a productive member of society.”

To that end, Owens concluded by asking the judge to sentence Hogue to probation or community corrections.

Arguing that prior probations had done little to change Hogue’s criminal behavior, and that the $17,000 in cash found in Hogue’s Xterra likely had been pilfered from Aspen businesses and locals, Oszczakiewicz asked for the maximum prescribed sentence for the most serious offense (three years for the possession of burglary tools), but added that she wouldn’t object to concurrent, rather than consecutive, sentences for Hogue’s lesser crimes.

At the moment of truth, Judge Seldin recounted each blemish on Hogue’s permanent record methodically, one after the other: Impersonating a 16-year-old at Palo Alto High School; the Utah prison stint for the theft of bike parts and tools; gaining admission to, and accepting a $22,000 track scholarship to Princeton, under false pretenses; a 1992 conviction for stealing precious jewels and gemstones from the Harvard Mineralogical & Geological Museum (where Hogue once worked as a security guard); arrests in Aspen in 1993 for stealing food and Rogaine from a grocery store, and in 1997 for bicycle theft; and an arrest for grand larceny in Telluride, where Hogue lived for a short time in the mid-2000s.

Adding that his most recent transgressions fit “the lifestyle of a career criminal,” Seldin ordered a six-year aggravated sentence for Hogue’s most serious crime, plus a three-year concurrent sentence for the other felony charge, and 138 days for the misdemeanor, credited to time already served.

“There is no indication that Mr. Hogue feels the rules apply to him,” Seldin said. “You’re a very consistent thief, Mr. Hogue, but apparently a very bad one because you get caught a lot.”

He asked Hogue if he had anything to say. Hogue responded meekly, “No, thank you.”

Instead of immediately being taken back to his cell, Hogue was ushered to a seat in the jury box. While the next sentencing hearing got under way, he sat there, visibly shaken. The con man, who at least twice had masqueraded as someone a decade younger than he really was, looked old.

X

Hogue’s demeanor changed after his sentencing. When I next met with him at the jail, among the many grievances he aired, he raved about the social injustices he believes are endemic in Vail and Aspen. One example of many: He once applied for a job as a lift operator; while reading the fine print of the health insurance provision in SkiCo’s employment agreement, he concluded that “the highest premiums and the worst coverage was for the lowest-paid employees, the ones who were most likely to need health insurance and the ones least able to afford it.”

It was a disingenuous observation from a man with a penchant for preying upon the lowest rungs of the economic ladder.

Just ask Andy Krueger, who was Hogue’s neighbor in Telluride in 2005, when Hogue committed the criminal act that landed him in the most legal hot water. Over the course of a year, Hogue accumulated about 7,000 stolen items valued at more than $100,000, covering the gamut from art to expensive rugs to sporting goods. He stashed the haul in a home he rented, a storage locker, a horse trailer, and a weather-tight cache he had excavated under an abandoned water tower outside town.

“I lived two doors away,” recalls Krueger, a freelance videographer. “Hogue was a serious runner. He ran all over the place. Seemed like a nice enough guy. We talked a bit, but he wasn’t real friendly. I was building an addition on my house and I started to notice that some of the lumber I had stacked in my yard was disappearing. At first, I wondered if maybe I was just not remembering how much wood I had. I started counting my boards before bed. Sure enough, someone was stealing from me.

“A few months later, Hogue starts building an addition onto the house he was renting, using lumber stolen from the people who were watching him work,” Krueger continues. “We couldn’t prove it. The landlord, who lived out of town, had no idea he was building the addition. Guess he needed the extra room to store all the stuff he stole. He was arrested less than two months later.”

That netted Hogue a 10-year prison sentence; he served only 4 years.

Krueger’s experience hardly seems to have been the first time Hogue had liberated items from folks of limited means. Although Hogue was never charged with the crime, Jim Davis now believes that while Hogue was in Vail, he stole an expensive bicycle from one of the other instructors at the camp. “The guy was just a ski bum who had saved up all winter to buy the bike and James stole it,” says Davis. “There was no one else who could have done it.”

X

Since his sentencing, I made a habit of calling the jail to see if Hogue was still in residence. The authorities do not tell inmates destined for the Big House when they will be taken away, and they generally don’t make that information public.

On April 3, when I phoned Detective Fain, Hogue was gone. “Guess this is the end of the Hogue saga in Aspen,” I said to Fain, who in May left the Aspen Police Department to take a job as an invistigator in the local District Attorney’s office. “We’ll see,” he responded. “He has a way of coming back here.”

Indeed: During our last visit in Aspen, when I had asked Hogue what his post-incarceration plans were, he said there was a good chance he would move back once he had served his time (he could be eligible for parole as early as January

20, 2020).

“Why?” I wondered incredulously. “You’re so well known here. You need a fresh start somewhere else.”

He just shrugged and flashed a wry grin.

And it became obvious. If you’re a professional angler, you go where there are fish. If you’re a lifelong grifter, you follow the money; in resort towns like Aspen, Vail, and Telluride, there’s plenty of it.

“I think he deserves whatever sentence he gets,” Jim Davis says. “He has been stealing from so many people for so long, including people who cared about him, that this has to stop. It has to stop.”

Before Hogue left Aspen, Detective Fain had wired $16,824.04—the total amount of cash recovered from the Xterra—to Hogue’s bank account. As for the high-mileage SUV containing all of Hogue’s personal effects: Since Fain didn’t know what to do with it, and since I needed a ride back to my home in New Mexico, I now own it; it literally will become the narrative vehicle for a forthcoming book about the Colorado high country’s most notorious con.