Mr. Chatterbox Revisits His Racist Past

I was born in a small town in northeast Texas called Greenville. It was about 50 miles from Dallas, and back in the old days it was a prosperous cotton town. In 1945, the date on my birth certificate, it had 25,000 people.

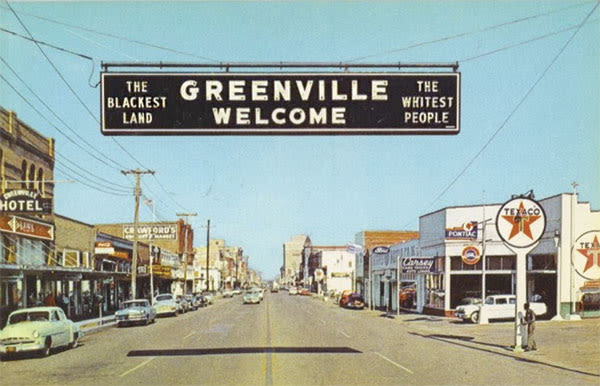

In most respects Greenville was a typical town for its time and place, but it had a certain kind of fame. It was known far and wide for the town slogan, which was strung across Lee Street and emblazoned on the water tower: “Greenville: The Blackest Land, the Whitest People.”

In Greenville’s defense, you have to remember that “white” had a whole other meaning then. It was the highest compliment you could give a person. It meant that he or she was above reproach. Honest and trustworthy and pure. And incidentally, probably white.

I didn’t grow up in Greenville, but my father did. Most of his childhood memories revolved around nostalgic slices of Americana: the cow they kept in the back yard or the car he bought as a teenager. But there were other stories, too, many of which had to do with the Klan.

Some were lighthearted, or as lighthearted as a story about the Klan can get. It seems that one of the big things about the Klan was secrecy. Klan members never revealed themselves to nonmembers. That’s how they were able to operate so successfully. (And believe me, they did operate. East Texas is the Deep South, and Greenville is closer to Arkansas, Louisiana and Oklahoma than it is to most places in Texas.)

At any rate, there was a prominent public official who became the joke of the town. Whenever there was a Klan parade down Lee Street, he would wear his trademark custom cowboy boots under his robe, instantly revealing his identity. All the people in town found this hilarious—the white people, anyway.

I’m glad to report that my grandfather, who ran the local cottonseed oil mill, was not a member of the Klan. In fact, there is a family story that he hid the local Catholic priest in the cabin out at the lake when the Klan was after him. Of course, this being a family story, it’s entirely possible that he hid the Klan from the local Catholic priest, but the fact that this story is never told in Greenville itself leads me to believe that it is true. It would not enhance his prestige, even today.

They took the sign down in the late ’60s. The cotton business died a slow death, and the enormous growth and prosperity of nearby Dallas-Fort Worth—now the largest metropolitan area in the South—missed Greenville completely. Other towns nearby have grown tenfold and are home to all sorts of tech and energy companies. But not Greenville. Nobody can figure out why.

When I was in Dallas recently for a family wedding, I had to drive out to Greenville to see for myself. This was sort of a bad idea, as it is now a sad and depressing place. When I would visit as a kid back in the 1950s, it was bustling with big cars and almost frenetic commercial activity. Now most of the buildings downtown are empty, and the architectural distinction that some of them had has been totally obliterated by misguided attempts at updating. Now they’re not only empty, they’re ugly, too.

The house my father grew up in is still there and in fairly good shape, though the neighborhood—once Greenville’s finest—has become very shabby. I could see the back yard where the famous cow lived, and I could still picture clearly what had been behind the living room windows. My grandmother had beautiful things, and as a small child I would stare in wonder at the bronze sculptures and the Tiffany vases and other artifacts from the 1920s that I was actually allowed to play with and that have shaped so much of my own aesthetic sense.

Next to the house was a driveway that proceeded through the porte-cochere to the garage at the back of the property. This was where one of my father’s favorite stories took place, and one, I’m afraid, that says volumes about the town’s racial dynamic. It’s a simple anecdote, designed to produce a chuckle: One of the “colored boys” would wash his car for a quarter. But he’d do it for free if my father let him drive it around the block.

The sign has been down for 50 years, but it stubbornly remains Greenville’s claim to fame. Looking around the town today, you can’t help but wonder if its humiliating decline is in some way connected to the hubris reflected in its slogan. Today Greenville seems too exhausted to deal with race. Besides, the cast is changing. Mexicans are moving in and, most astonishingly, an enormous Nigerian church, with branches throughout the world, has chosen Greenville as its U.S. headquarters. (The pastor says God told him to, and besides, the price was incredibly cheap for all that land.)

So now, just outside of town on Highway 380, there sits a sort of convention center/megachurch that seats 10,000, with plans for more buildings, including a university and a housing development. Every June, motels for miles around are packed for the church’s Reunion Weekend, with worshipers from around the world, including a large proportion of the Nigerians who run the church. There is talk of a stadium/worship place that would hold 100,000. With millions of members who are encouraged to tithe heavily, this is entirely possible. Greenville’s reaction? I’ve never once heard my relatives so much as mention it.

There was one more place I had to see. My grave. Yes, there is a family plot in Forest Park Cemetery, and right next to my parents’ handsome black granite tombstone is a place for me. Should I take it? It’s there and it’s paid for. But it’s not very pretty and it’s too close to the highway. And most important, do I want to spend eternity buried in the blackest land among the whitest people? Probably not, so I’m thinking of putting it on the market. It would be a great buy for a Nigerian named Plunket.