90 is the New 60

Anyone who doubts the face of age is changing need only spend a few days in Sarasota. From the gym to the office, from nonprofit boards to the tennis courts, men and women decades past retirement age are leading active, engaged lives, contributing energy, talent and wisdom to us all. As sociologists have documented, the world is getting older, and those 85 and over are the fastest-growing segment of the global population. Nowhere is that more apparent than right here at home, where more than 10,000 people 85 and older reside within our county lines. Yes, they may have more aches and pains with advancing years, and nearly all have suffered some of the losses that time brings. Yet legions of them still greet each day with excitement and declare they still have more to give. Meet just a few.

Shirley Goodman

At 93, Shirley Goodman is still dancing through life. The effervescent Goodman teaches three jazz line dancing classes, tap lessons at two nursing homes, and performs at weekly jam sessions at 15 South Enoteca. “I have groupies,” she quips.

Goodman’s father, a vaudeville musician, taught her to tap dance at 8. “We had no money, but we had so much music and love in our family,” she says. Dance remained part of her life as she married and raised four children with her husband, Alfred Goodman, who was president of the Sealy Mattress Company. After he died, she says, “Dancing saved my life.”

Attitude is everything in dealing with the losses that advancing age can bring, says Goodman: “It affects you physiologically.” She gets out of the house every day, and drives herself everywhere she needs to go—to restaurants, too, as she considers “cook” a four-letter word.

Last month, at the Clearwater Jazz Festival, the familiar sound of tap dancing led her to a group of students rehearsing. “I said, ‘How’d you like to see what an old bag can do?’ They went crazy and asked me to be in their show.” So Goodman danced at that high school show and got a standing ovation. “It was a thrill—something I’ll never forget,” she says.

What’s hard about being 93? “I have only one friend from my original social group. She’s 98, looks stunning, is sharp. But she’s hard of hearing so she doesn’t talk on the phone. I joke I should make younger friends—in their 80s.” Advice for the folks? “Be happy. Keep smiling. Keep dancing.”

Dr. William Weiss

The stereotype is that senior citizens spend lots of time at the doctor’s office. And that’s certainly true for Dr. William Weiss, 93. But Weiss, a retired allergist, isn’t there about his own aches and ailments. Instead, the energetic Weiss is there to see and treat other patients. For the past 18 years, Weiss has been working as a volunteer physician at Sarasota’s Friendship Centers, seeing patients two days a week.

Weiss attended New York University College of Medicine in the early 1940s, served in the military during World War II and ran a private practice in New Jersey for more than 40 years. He and his wife, a retired teacher, had spent time vacationing in Sarasota and loved it, so in 1992 they decided to make Longboat Key their permanent residence.

In addition to seeing patients, Weiss remains actively involved in medical research. Recently, his research on the “pulmonica”—a harmonica that helps people with COPD breathe easier—earned him a spot at the COPD9USA conference last June in Chicago.

And his interests don’t end with medicine. Weiss, who says he’s always been skilled with a hammer, has also volunteered with Habitat for Humanity for more than 20 years. “I only stopped getting up on a ladder two years ago,” he says, but he’s still helping out as part of the building crew.

Hobbies? “I love sailing and I used to do a lot of waterskiing, but people stopped wanting to go with me because I’m too old!” Secret to longevity? “In addition to good genes, I follow the Mediterranean diet and haven’t eaten red meat in 40 years.”—Megan McDonald

Louis Cabot

Since Louis Cabot retired 15 years ago, he’s been chairman of the America’s Cup Foundation, chaired the Brookings Institution and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and served on the Council on Foreign Relations. Cabot, now 94, also took up photography, and has become professionally successful, showing and selling his painterly, bird-infused landscapes at the Longboat Key Center for the Arts, Ringling College of Art and Design and the Island Institute in Maine, donating the proceeds to environmental preservation causes. At an exhibition of his work in Maine in 2015, one buyer snapped up all 29 of his pictures.

His father gave Cabot a Brownie camera when he was 10, sparking a fascination that waited decades to be fully indulged. He spent the intervening years running his family’s company, Cabot-Wellington, LLC, and also served on various national and international boards.

The advent of digital photography allowed him to transform photographic images into dreamy canvases awash in light and motion. Today, Cabot has nearly 100,000 images in his computer and spends hours in the studio at his Longboat Key home editing them—when he isn’t out capturing the landscape through his lens. A state-of-the art printer, bulletin boards pinned with proofs and walls covered in birds in motion testify to his industriousness.

After years of worldwide travels and a glittering social life, Cabot and his wife, Muffie (former social secretary to Ronald Reagan), now say a perfect evening starts with settling down on the beach or a dock just before dusk falls. “We just sit and watch the evening come on,” says Cabot. “Sometimes we see the sunset and sometimes we don’t. It’s glorious.”

A golden time? “I was a young American [in England just after World War II] at a time when every Englishman was delighted to meet an American. It was a wonderful period.” Any regrets? “I wish I’d met Muffie 75 years ago.”

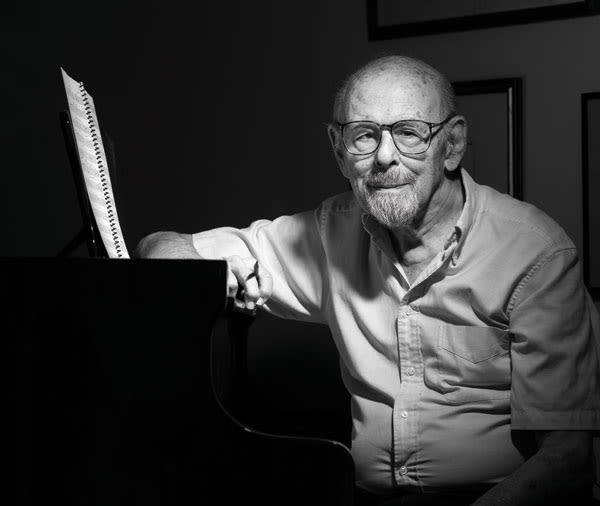

Tommy Goodman

At 91, musician and composer Tommy Goodman plays with a trio every Friday night at Burns Court Café, jams every other Tuesday at the Allegro Bistro in Venice; plays in a trio at the First Methodist Church jazz series, and is in a sextet and quartet with the Sarasota Jazz Club.

“My whole life has been music,” says the twinkle-eyed Goodman, who moved to Sarasota full time five years ago with his “jazz moll,” artist Lilli Montezinos, 89.

Brooklyn-born Goodman was playing advanced classical pieces in elementary school. When he was about 10, he discovered jazz. “It hit me in the stomach,” he says. For the rest of his life—through his education at the Eastman School and Yale, and later with famed musician Nadia Boulanger in Paris—Goodman would be bewitched by the twin siren calls of classical and jazz music. His chameleon-like ability to adapt to a multitude of styles earned him posts in the Armed Service Band during World War II and later, on Broadway, where he played the piano for musicals from Silk Stockings to The Unsinkable Molly Brown. There was also a long and profitable career writing music for TV and radio and movies.

He still teaches and enjoys writing, sometimes little compositions for special occasions, or more ambitious projects for himself. Currently, he’s wrapping up an eight-minute piece he calls Variations and Reflections on the Jitterbug Waltz (by Fats Waller).

“It’s so mysterious; it cuts so deeply,” Goodman says of music. “Life [can be such a] heavy experience. If you’re fortunate enough to be gifted with one of the arts, you have to respond to it. You can’t keep it in.”

Vices? “I have a [refrigerator sticker] that says, ‘Wine is cheaper than therapy.’” What’s good about being in your 90s? “I wake up in the morning, and I’m still here.” What’s difficult? “Losing people. And it’s harder to do the traveling—the schlepping, the waiting in lines.” Life advice? “Try and be reasonable in everything, [including] in relationships. Don’t give up too easily.”

Glossie Atkins

Neighborhood kids walking past the tidy Newtown bungalow know they must answer the call of the lady sunning herself in her yard with two little dogs at her feet and a Bible on her lap. She fires off the questions: Did they go to Sunday school that week? Do they know who’s really in charge of their lives? She may be 98, and her knees may be giving her trouble, but that hasn’t kept the indomitable Glossie Atkins from volunteering at church and the Robert Taylor Community Center—or from keeping a watchful eye on passing children.

Fifty-three years ago, when Atkins moved to Newtown, African-Americans couldn’t patronize many downtown stores or restaurants. “Oh, but it’s changed a lot,” says Atkins—who went on to see her son, Fredd, twice elected mayor of Sarasota.

Atkins grew up on her parents’ farm in Ocala, and she fondly remembers Sunday mornings when her mother would load up all the kids and a big picnic in the back of a two-horse wagon and drive them to spend all day in church. She came to Sarasota to pick fruit on farms, then worked as a domestic to support her seven children. She jokes that she never retired; she had to quit because she outlived all her employers.

Today, Atkins remains enmeshed in the community she loves, a beloved icon to friends and family. And she’s still a gifted cook who serves up bread pudding and sweet potato pie at neighborhood events.

Where do you most love to be? “At home in my yard.” What’s hard about being 98? “Not being able to care [for] my flowers. It makes me sick to see them like this.” A favorite pastime? “Music, especially spirituals. I like to sing, but I can’t sing!”

William Murtagh

He doesn’t own a computer anymore and has a pacemaker and some medical challenges, but for people passionate about historic preservation, 92-year-old William Murtagh is still the man. “I get calls all the time,” says Murtagh, who lives in Lido Key’s retirement community, Plymouth Harbor.

Murtagh still lectures about his life’s work: establishing national guidelines to identify and preserve historic resources. He’s still receiving awards, too; in December he flew to Washington, D.C., to be honored at two black-tie events for his contributions to the International Council on Monuments and Sites.

As an architecture student when Bauhaus was all the rage, Murtagh traveled to Rome and marveled at the Pantheon. He thought, “You can’t call this a lousy building. There’s something wrong with my education.” So he earned a master’s in art history and a doctorate in architectural history, going on to become Keeper of the National Register, director of the Pacific Preservation Consortium and the Historic Preservation program at Columbia University and president of the Victorian Society of America.

“Retirement” has meant decades of lecturing and writing, including completing his seminal work on historic preservation, Keeping Time (he funds scholarships with the proceeds). Although he says he’s unsure whether he can continue to summer in his Maine seaside cottage, Murtagh still begins every day on the exercise bike and enjoys a splash of rum before dinner.

Career advice for students? “You never know where you’re going to go and you can always get off [the track you’re on] if you want.” What’s hard about being 92? “You’re extremely conscious of what’s coming down the pike, and whether it’s going to incapacitate you or not.” What’s good about it? “You can get away with murder.”