Coping with Caregiving

Interview by Hannah Wallace

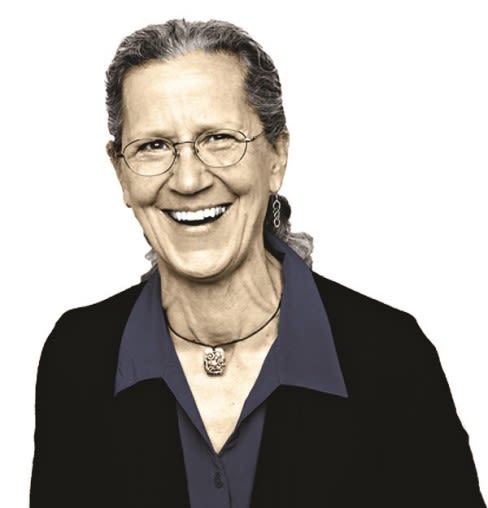

Dementia expert Teepa Snow on the caregiving crisis—and why Sarasota is ahead of the curve.

In a rapidly aging world, caregiving for seniors, especially those with dementia, has a major economic impact. Lost labor due to physical absence and emotional stress affects every business, and many companies are ill-prepared to manage and help employees who are caring for a loved one. Additionally, service industries need guidelines for dealing with customers who have dementia, so that they and their caregivers will feel welcome.

Teepa Snow is a national expert on dementia and caregiving. Her natural empathy first found purpose working with developmentally disabled children. But after living with an aging grandparent and later acting as a caregiver for her mother-in-law, Snow devoted herself to advocating on behalf of people with dementia and acting as a mediator between them and their caregivers. She now travels more than 300 days a year, training professionals and laypeople alike to better understand dementia and how to manage their relationships with patients and loved ones. Locally, Snow partners with Pines of Sarasota, providing educational materials and regular speaking engagements.

Why do you focus on the caregiver/patient relationship? People who live with dementia die with dementia. They’re not around to talk about the experience. The caregivers, too, when it’s over, they’re so exhausted they don’t want to talk about it. Until we have a cure, we have to have better ways [to manage this relationship]. We need to know how and what to do.

What’s it like being a professional, a woman, and a caregiver? It never stops for women. They get up in the morning and then they have to take care of the person they care about, take them to where they need to go. And then at the end of the workday they feel this urge to be present for this other person. They’re already running on empty and not taking care of themselves. I certainly did that during my mother-in-law’s care. There was no one [else] who could be tolerant of her, because she was a challenge. You do what you think you need to do until you can’t do it anymore. Nobody steps forward to say, “Let me carry that for a while.”

How can caregivers create stress relief? You need to build it into every day. And you have to stop seeing it as a benefit. If you don’t respect yourself, you’re not going to be there for your loved ones. You’re setting up somebody else to be your caregiver.

It starts with little tiny stuff. Use cleansing breath—take five deep breaths, and then give yourself a minute to think of one thing that you feel joy for. Do that five times a day. Then, when you feel the stress, guess what automatically comes to you. It retrains your brain into finding those moments of joy.

What’s the state of professional care for those with dementia? It’s horrendous. The federal government and the state don’t require special skill sets as a rule. [Most professionals] take a six-hour [dementia] course—they watch a video—and that provides you with everything you need to care for someone who has a brain-changing disease? Even in [memory care] residential programs, professionals don’t necessarily have special skills. Then the patient escalates because she’s not getting her needs met, and they may give her medications to make it difficult to act out. It becomes this horrible cycle.

In Florida: 500,000 seniors with Alzheimer’s require 1.1 million dementia caregivers.

When should caregivers consider moving their loved one to a residential facility? I usually ask, “Tell me what you still like about your person.” When the caregiver answers, “Well, I love them and I promised I’d always care for him,” I say, “I know you do. But what do you like about them?” There’ll be another long pause, and then they’ll say, “I lost my mom/husband/wife a long time ago.” So I say, “The time you should place [them in a facility] was about three months ago. You’ve given everything; it’s not changing the disease. You need a break, so you can recover.”

What can business owners do for employees who are also caregivers? Businesses can allow the individual some flexibility in scheduling if possible. [For example] take into account drop-off and pickup time—is there a way we can work this out so that I don’t have to get [my loved one] up three hours earlier?

What about dealing with customers with dementia? Are people with dementia welcome in the establishment? Can we have dementia-friendly locations so that if my mom makes a mistake, we still feel welcome? If not, then where am I supposed to go? If something happens, [the business staffer] should consider that dementia might be what you’re looking at, and here are some options for what to do. We’ve done it with other conditions. We now have a better awareness of when kids have autism—you recognize it when you see it, and you understand that more than likely touching is not a good idea. We need the same awareness of dementia.

How can employees communicate with someone who has dementia? [People with dementia] get such a reputation. But when do they get angry and when do they get aggressive? Pretty much when people keep trying to do things that aren’t working, and they’re not listening. We always want to ask direct questions. But when you ask a direct question, the person [with dementia] gets stumped, so they try to leave. You tell them to stay, they say, “Don’t tell me what to do.” Sometimes it’s just a matter of being friendly and saying, “Well, hey there, where are you from? Do you live in town? Hang on a sec, I bet we can get you where you need to be.”

How well is Sarasota handling this issue? Sarasota is having to address this a lot faster and harder than a lot of communities. There has been work done by the police, by the EMS, that other communities haven’t even begun to address: They’ve participated in training, asking, “What can we do?” and starting to learn some skill sets. Sarasota’s also really tuned into the fact that aging in different cultures really matters: Mennonite versus Hispanic versus the art guild—what you would see [in dementia patients] behaviorally is different, but it’s still dementia. ■

Dementia’s Impact

1 in 3 seniors dies with some form of dementia

In 2015, 700,000 will die with Alzheimer’s

5 million Americans have Alzheimer’s (60 percent are women)

$226 billion--Amount dementia will cost the country in 2015 (projected as high as $1.1 trillion in 2050)

1 in 5 Medicare dollars is spent on people with dementia

17.9 billion hours--Unpaid care provided by friends and family to dementia patients in 2014

41 percent of caregivers have a household income of $50,000 or less

Two-thirds of caregivers are women

Teepa’s Tips

How to approach a person with dementia.

• Knock, announce yourself.

• Greet and smile.

• Move slowly, offer hand for a handshake.

• Give your name.

• Slide into a hand-under-hand hold.

• Be at eye level with the person.

• Be friendly, smile, give a compliment or make a nice comment.

• Give your message—simple, short and friendly.

Visit pinesofsarasota.org/pdfs for more of Snow’s tips, techniques and downloadable training guides.