New Topics New College: Climate Change with Jeff Chanton

The word “glacier” doesn’t immediately invoke thoughts of Florida, but thanks to climate change, the two are becoming increasingly linked, says Jeff Chanton, professor of oceanography at Florida State University and a 1975 graduate of New College of Florida.

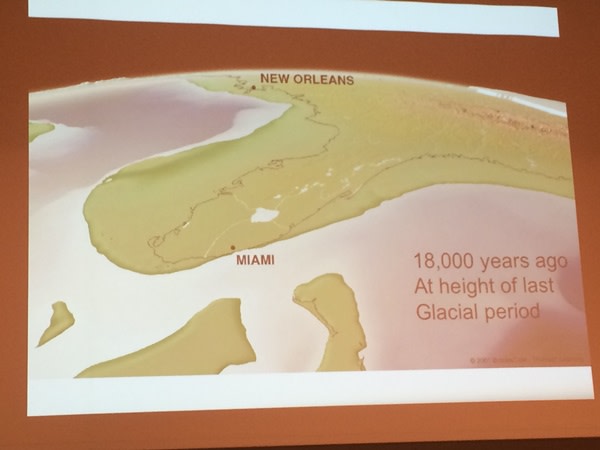

Chanton returned to his alma mater yesterday for “Florida: The Canary in the Climate Change Coal Mine,” a talk that focused on how sea level rise affects our state (spoiler: it affects us a lot). In just the last 18,000 years—a blip on the global history scale—sea level has risen approximately 300 feet. Current trends estimate that we will lose another 8 to 12.6 inches per century as ice sheets, permafrost and glaciers melt, says Chanton.

Global warming from greenhouse gas can be likened to a parked car, he says. The windshield is transparent to the visible radiation from the sun, absorbed into the seats of the car and re-radiated as infrared radiation, or heat. The windshield keeps these rays from escaping, warming the inside of the car. The earth—its atmosphere, hydrosphere and troposphere—work similarly; imagine the atmosphere to be the windshield, the hydrosphere (or oceans) to be the seats and the troposphere (solid earth) the inside of the car.

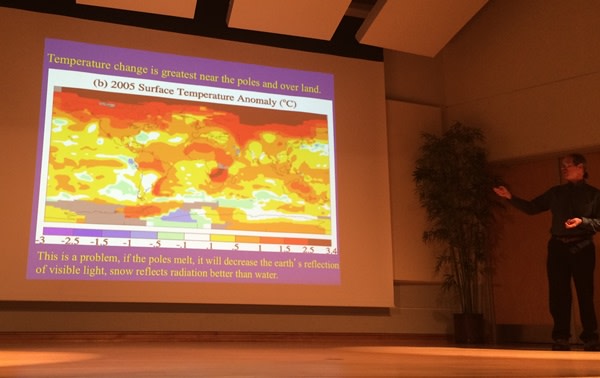

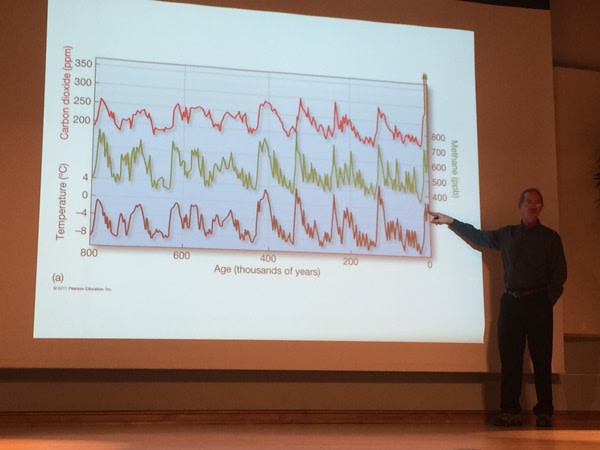

“Changes in sunlight associated with the earth’s orbit [influence global warming],“ Chanton says. “The sun gets a little brighter and warms the ocean, degassing CO2. When it degasses, it causes the planet to warm up a little more, so it degasses more CO2 in a positive feedback loop.” The warmer Earth’s temperatures get, the more ice melts, releasing trapped CO2 and methane into the atmosphere and providing more water to absorb the visible radiation. Ice, on the other hand, traps the gasses and reflects the rays back out into space, keeping the global temperature lower.

Today we’re living in an interglacial period, meaning the ice caps are receding and the earth and its oceans are warming. Scientists have witnessed patterns of the last five glacial and interglacial states through ice coring—measuring trapped atmosphere in large chunks of ice pulled from beneath earth’s crust—and have found that they’ve all occurred over the last roughly 400,000 years.

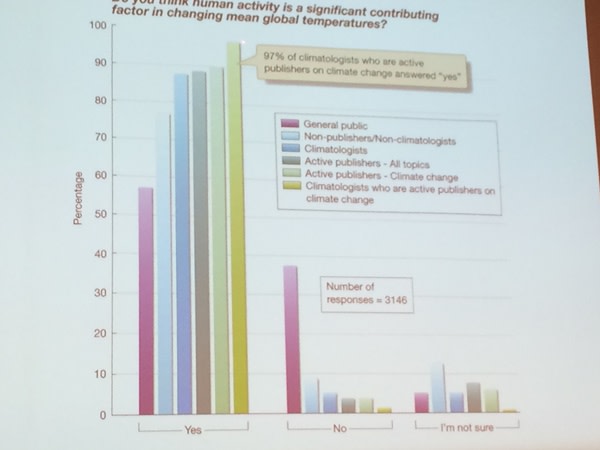

While there is no definitive answer on how to retroactively correct the damage done, there is some good news: The number of people who believe that climate change is a pressing global issue is on the rise, too. “What’s tricky for us as humans and having a large population is change. We have to be aware of what can change and then respond accordingly,” Chanton says.

Go here to learn more about New Topics New College.