Legal Advice for Trophy Wives, Stepchildren and Other Sarasota Family Issues

Karen Smith (not her real name) returned home to Sarasota a few years ago and received some unwelcome news. Her stepchildren were suing her, alleging that she had manipulated her late husband into cutting them out of his $5 million estate. John Smith, a Fortune 500 retired executive, had died in his early 90s, after being married to Karen for more than 30 years.

"If I weren't 1,000 percent sure of myself, I would not have been able to get through it," Smith, who is now in her 70s and has grown children from a previous marriage, says about the two-year legal battle that followed years of caring for a husband with dementia. The stepchildren hired detectives, subpoenaed health care workers and dragged trusted friends and household workers into the fray.

The changes John Smith made to his estate documents several years before he became ill were prompted by a family disagreement, Smith says. "He was a very bright, kind man and always wanted to protect everybody," Karen says about her husband, who managed all their money. For years he tolerated his children's ill treatment of his wife, she says, but after a dispute over shared assets, he became convinced his children were concerned only about "money, money, money." Smith says that after the falling out, she urged caution and told her husband to "sit down, sit down and think about your grandchildren."

But John was determined. He hired an estate attorney and, prior to changing his documents to leave his entire estate to his wife, visited his doctor for an exam to prove he knew what he was doing.

The Smith family turmoil underscores the legal, financial and emotional complications that can accompany second marriages, especially when the couple brings children and wealth to the new relationship. Wealth advisers and attorneys say the Smiths are far from unusual, especially in Southwest Florida, where second marriages are common.

"When there is a significant age difference between spouses, and the spouses have separate children from prior marriages, the situation is ripe for conflict," says Benjamin Hanan, an attorney and certified public accountant with Shumaker, Loop and Kendrick, LLP. "I have clients who change their will frequently, depending on how they feel about their children. I don't know if they tell the children."

Documents can be drafted clearly, but that still may not stop someone from claiming "undue influence" or that a person lacked mental capacity when signing estate documents—two ways to challenge a will in Florida.

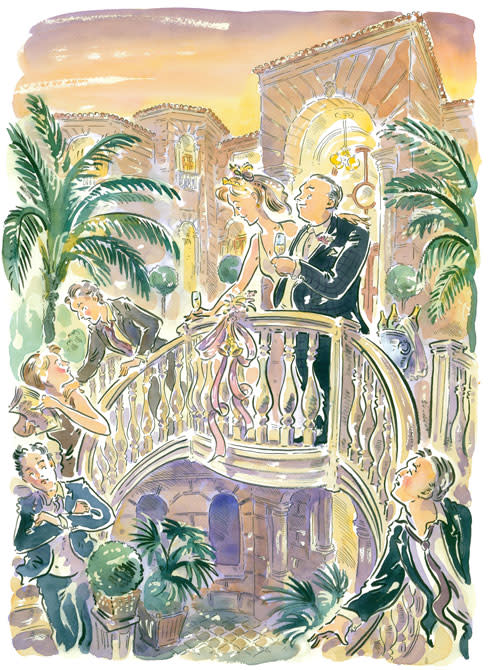

For new spouses, marrying into wealth can be a "giddy experience," says Suzanne Atwell, a licensed mental health counselor who had a private practice and counseled a number of wealthy women before becoming a Sarasota City Commissioner. "It's a fascinating system that swirls around wealthy blended families. There are all these accouterments—vacation homes and gorgeous gowns and galas. But there is so much going on behind the scenes. If you are marrying into it, you better figure out the players and how you fit in that family dynamic."

"Adult children can resent the new wife and see her as a gold digger," says Rachelle Katz, a New York licensed family therapist and author of The Happy Stepmother, a book that counsels women how to adapt to second and third marriages. "There is a kind of insecurity…they feel they are losing out."

The Smith children had an uneasy relationship with their father and stepmother from the beginning of their marriage. When John Smith married Karen, he was close to 60 and had been separated from his first wife. Karen was a divorced mother in her 30s. He treated her children as if they were his own and never asked her to sign a prenuptial agreement, despite his wealth.

His own children were not subtle about showing their resentment, Smith says. She sent them Christmas presents; they sent gifts only to John.

"I tolerated them; they were my husband's children," Karen says. "I knew they didn't like the marriage. But I was good to them. I just got to a point where I didn't let things bother me."

When John started showing signs of dementia, his children became frequent visitors. They tried to arrange private meetings with his attorney and insurance agents. A home health nurse told Karen that when she left the house, the stepchildren rifled through drawers and peppered her with questions. "They harassed me and harassed me," Karen says.

After John Smith died, his children were shocked to learn that he had removed them as beneficiaries. They demanded their father's financial and medical records and hired a detective. Three years later, they filed the lawsuit.

Florida law does not entitle adult children to inherit from parents. So the children had the burden of proving that their father was not mentally competent when he changed his documents. "It is difficult to challenge a validly executed will in Florida," Hanan says. "The law wants to respect the intentions of the testator"—the legal term for the deceased.

After two years of court battles and hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal bills, Smith says she had had enough. The family settled. Karen demanded a written apology as part of the settlement and agreed to set aside money for the grandchildren.

Before families fight over the will, they often experience years of conflict. With second marriages can come resentful children and differing expectations of marriage and the role spouses expect one another to play in their children's lives. About 65 percent of second marriages end in divorce, significantly higher than first-time marriages.

That is one reason why wealth advisers recommend a prenuptial agreement, especially if there are children from a first marriage. Attorneys say it is easier if both people bring similar assets to the marriage.

"Generally it's, 'You come in with what you have and leave with what you brought,'" Hanan says.

Prenuptial agreements can get dicey when the future spouses have unequal assets. Take a wealthy older man and pair him with a younger woman of modest means, the so-called "trophy wife," and you can have some prickly discussions. The man may have a bevy of advisers, while the woman may be inexperienced and alone.

"She needs to protect herself," says Art Ginsburg, a family-law attorney with Icard Merrill, who has handled many prominent divorce cases. "She can't just think, 'Oh, I can talk him into anything after we are married,' or that he will always take care of her."

Spouses are often afraid to question a prenuptial agreement because they do not want to be perceived as marrying for money. Ginsburg says he has had clients come to him after agreeing to as little as $1,000 a month in a prenuptial agreement and then getting stuck with that amount in a divorce settlement.

Florida law calls for the equitable distribution of assets accumulated during the marriage. But that right could be signed away in a prenuptial agreement. Ginsburg had a male client who married a wealthy woman and agreed to forego any right to increases in her stock portfolio. The value of her Coca Cola stock alone soared during the marriage, growing to $25 million. Then the wife found someone else and asked for a divorce. The husband tried, unsuccessfully, to overturn the prenuptial agreement.

"He lost out on all that stock," Ginsburg says.

Attorneys say future spouses of unequal means should look at a prenuptial agreement for fairness.

"If someone is worth 50 million bucks and asks his future spouse to sign an agreement for 1,000 bucks a month, that's not right," Ginsburg says. "What kind of future partnership is that?"

He says that people should review prenuptial agreements a few years into the marriage to reflect a change in circumstances, such as the birth of a child or an illness. Ginsburg advises clients to include a provision requiring the wealthier spouse to cover college costs for any children the couple has together. In Florida, divorcing spouses are not automatically required to pay college costs for children.

Experts say that people marrying for the second or third time have to ask themselves a lot of "what if" questions when it comes to planning their futures.

"It is shocking to me how uncomfortable people are about talking about money and wills," says Katz. "A lot of women are uncomfortable asking, 'What happens if you die?'"

Katz operates a message board on her stepsforstepmothers.com site. It is filled with second-wife angst about children, exes and financial issues. One 43-year-old woman recently posted that she was jolted when her 53-year-old husband casually said one day he was leaving all his assets to his kids.

"This shocked me to my core," writes Ilovepuck, who has no children of her own. "We talk about how we are going to retire all the time. I am bringing about 1/3 of assets in. If I die before him, he and his kids will get everything, but if he dies before me, apparently I don't. So my retirement quality of life doesn't count if he passes before me?"

Then there is the other end of the spectrum—spouses who do not consider their children when they remarry.

"We see everything in our office," says Jim Germer, a CPA and financial advisor with Cetera Financial Specialists in Bradenton. A new marriage involving an aging parent is a common scenario in Southwest Florida with its large population of retirees. Sometimes the aging parent will focus on his or her new spouse and lose interest in the children from an earlier marriage.

"It's a big source of friction with family No. 1," Germer says. "There are some second spouses that will wear down a new spouse to change their will and trust documents."

Germer says one 92-year-old client, a retired pilot with four children, recently came into his office to say he's getting married to a 70-year-old woman.

"He lost his wife a few years ago; he fell in love again," Germer says. "It's my job to steer him to consider the financial issues, so I made a joke and asked, 'Are your kids happy about this?'"

The children were not happy.

Adult children often have to straddle a line between wanting their elderly parent to have companionship and protecting their inheritance.

"If they speak up and say too much, they may upset their father and risk getting disinherited," Germer says. "They have to maintain good relations with the new spouse."

Parents should have a conversation with their children and spouse and be clear about his or her intentions. Germer says there are ways to arrange assets to take care of everybody. The wealthy spouse's assets could be put in a trust to benefit his children but set up in such a way that the second spouse could live off the interest until his or her death, with the assets then passing to the children. Life insurance policies are another strategy. In Florida, a spouse cannot be disinherited and is generally entitled to one-third of their spouse's estate, including anything given away a year prior to death.

Successful second families navigate such legal and personal land mines with open communication about money and values. They are not afraid to disagree and hash things out.

"It is very complicated, and every stepfamily is unique," Katz says.

To read about more about wealth in Sarasota, click here. >>

This article appears in the March 2014 issue of Sarasota Magazine. Like what you read? Click here to subscribe. >>