Should Florida Exterminate or Accommodate Invasive Species?

Silhouetted against the moonlight, the strangest lizard I had ever seen hung on my porch screen. A foot long from head to tail, with wide golden eyes and a baby-blue body with bright tangerine spots, it looked like something a child might draw with a big box of crayons. I caught it with a mixing bowl and a Van Morrison Moondance LP sleeve and placed it in an empty cardboard box. It was big and beautiful and angry. I named it Gloria.

I grew up in Southwest Florida catching lizards, snakes and frogs, but never had I seen a creature like this. A quick internet search revealed Gloria to be a tokay gecko—a voracious rainforest species from Southeast Asia that outcompetes, displaces and eats native Florida geckos and other lizards. Like the Burmese pythons that gorge on Everglades wildlife—in just a few decades, they’ve wiped out some 90 percent of the mammals that once thrived in the Everglades—Gloria is a part of a scourge of invasive species spreading throughout Florida.

Now that I had Gloria in my possession, I wasn’t sure what to do with her. I learned that it would be illegal for me to release her back into my downtown yard—or anywhere in Florida. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC) website recommended that I euthanize her humanely. But how serious was the gecko’s trespass? Did she merit execution? I had to find out.

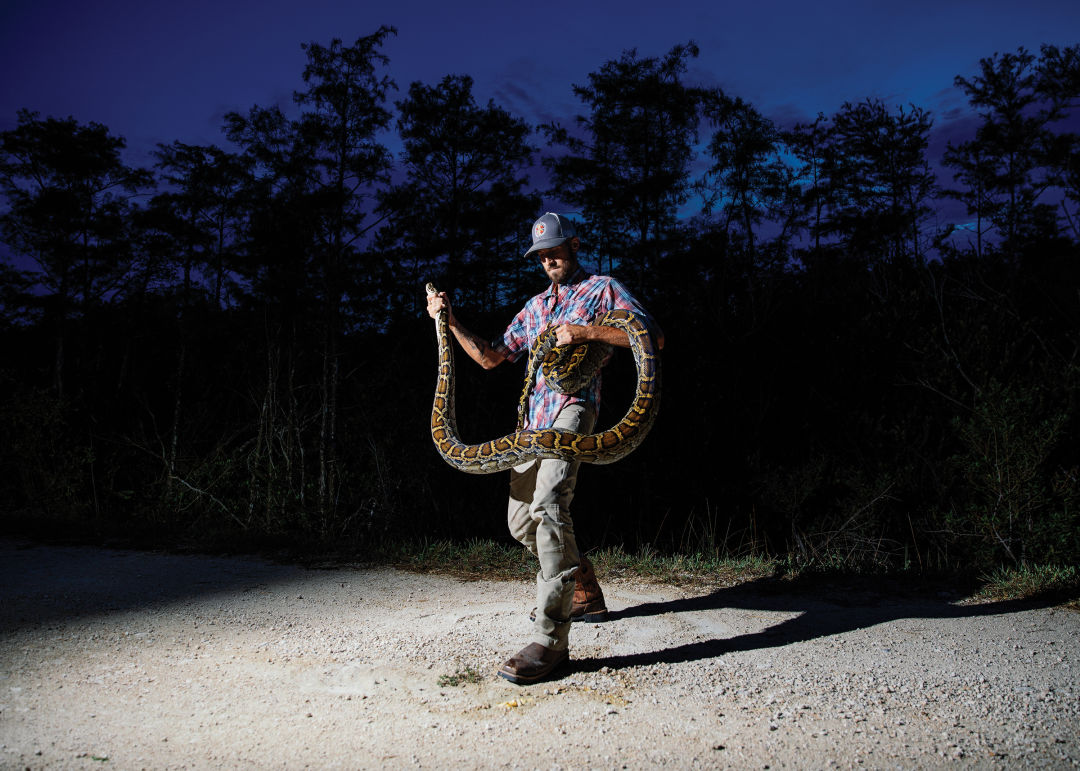

Tens of thousands of Burmese pythons inhabit the Everglades.

The first thing I learned is that what is and isn’t labeled “invasive” depends on a species’ behavior. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Invasive Species Information Center identifies an invasive species as a plant, animal or microbe that is alien to an ecosystem and “whose introduction is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.” That explains why honeybees, which are vital to U.S. agriculture, aren’t considered invasive even though they are native to Europe.

Florida consistently ranks as one of the top five places in the world with the most invasive species. And the state is the world epicenter of invasive reptiles. In fact, non-native reptile species now outnumber native reptiles by 3 to 1 in Florida. According to state agencies, as of 2019, 194 invasive plant species and 126 invasive animal species lived in Florida.

What brings so many unwanted newcomers to the state’s shores? First, Florida is young. The state was underwater for most of its history. The Everglades is just 5,000 years old. Compare that to, say, the Appalachian Mountains, which were formed 480 million years ago. Florida’s brief existence has allowed less time for new species to make their way here and interact. Compared to other wet and green subtropical climates. Florida has relatively few native reptile species. For instance, while Florida has 16 species of lizards, Brazil has 248.

Florida is also geographically inconvenient. For millennia, the only immigrants from the tropical south were birds and the occasional frog, lizard or insect that hitched a ride on detritus from an island after a big storm. Otherwise, Northern species colonized the peninsula.

But the main reason for Florida’s invasive problem is the plant and animal trade. More exotic plants and animals are legally and illegally transported through the ports of Florida than anywhere else in the country. Most of the state’s geckos—including Gloria—are the descendants of escaped forebears of this billion-dollar industry.

Horror stories about invasive animals saturate the media—pythons swallowing alligators in the Everglades, rhesus macaques in Orlando carrying a deadly strain of herpes, insatiable lionfish devouring reef life in the Gulf of Mexico. But a greater danger may be invasive plants, such as cogongrass, a weed from Southeast Asia that needs only a few inches of clippings to root and spread; the melaleuca tree from Australia, which stores as many as 20 million seeds that can remain viable for 10 years; and an Old World climbing fern that grows up to the top of the canopy and suffocates entire forests with a thick, green shroud.

This is of great concern to the state. These newcomers can damage ecosystems and destroy native wildlife, threatening the economy and even human health. Unpredictable things happen when organisms from different ecosystems first brush up against each other. Some scientists have theorized that the coronavirus pandemic sprang from the cramped intersection of wild animals from disparate places in a Wuhan market, with the virus perhaps leaping from bats to other animals and eventually to sellers and customers.

Invasive species cause $137 billion annually in damages to U.S. industries and infrastructure. The National Park Service and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC) estimate that Floridians spend more than half a billion dollars per year trying to manage the crisis. They say it’s not nearly enough.

And legislative attempts to control invasive species can face pushback. In June 2020, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law SB 1414, which prohibits the sale and breeding of green iguanas and tegus, a large lizard from Argentina. The United States Association of Reptile Keepers’ Florida Chapter and six individual plaintiffs are challenging the constitutionality of the new law, citing “irreparable harm” to their industry.

The rhesus macaque has found a home in Central Florida

Image: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock.com

I called Steve Johnson, a professor at the Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation at the University of Florida whose specialty is natural history and the conservation of amphibians and reptiles, to get his take on what I should do with Gloria.

He agreed that euthanizing her might be a step in the right direction—but a tiny step on a near-endless journey.

“If everyone removed invasive plants and animals from their yard on a regular basis, we’d see some positive change,” he said. “But removing them is not a one and done thing. It’s like maintaining your lawn. You have to keep mowing because the weeds keep coming, and that’s the same with invasive species.”

“If I do decide to—remove her, what’s the best way?” I asked.

“Research dealing with euthanizing cane toads concludes that anything that is a tropical or subtropical adapted species is most humanely dealt with by sticking it in the refrigerator for a couple of hours,” he said. “Then put it in the freezer.” Cooling in a fridge slows down the chemical reactions in the body and avoids forming ice crystals that might penetrate the cell membrane and cause pain. “There are other humane methods,” Johnson said. “But they are a lot more grotesque.”

Still, tossing Gloria in the fridge didn’t seem like yanking out a dandelion to me.

I looked for a second opinion from Stephen Enloe, a professor of agronomy at the Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants at the University of Florida. He didn’t share my moral dilemma about removing invasives. His field is plants, and he would love for people to murder invasive vegetation. Invasive flora is a far greater threat than alien fauna, said Enloe. He sometimes feels like Sisyphus, and I imagined him rolling an invasive Australian pine tree up a hill only to have another sprout in its place.

And then there’s the Brazilian peppertree. Brought from South America as an ornamental plant in the 1840s, it now covers more than 700,000 acres in Florida. It crowds out other plants and creates inhospitable conditions for native species, reducing Florida biodiversity and ecological health. Conservationists have a whole host of tools at their disposal to remove Brazilian pepper and other invasive plants. They pull them out by their roots. They introduce other non-native species that prey on them. The air potato plant population, for example, has been significantly reduced thanks to the intentional introduction of another invasive species—the air potato leaf beetle, which they had studied for years to make sure it wouldn’t negatively affect other organisms.

Mostly they use herbicide; the most common is the controversial glyphosate. The chemical has come under international scrutiny and has been suspected of having carcinogenic links, but the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) agrees with the EPA’s assessment on glyphosate as a safe herbicide. “We use surgical precision when applying glyphosate,” Enloe assured me.

But despite all those methods, completely eradicating Brazilian pepper has not been possible, he said. It’s here to stay.

Enloe believes the best approach is to prevent invasives from getting here in the first place. “We have millions of acres in Florida that are relatively intact,” he said. “So it’s important that we continue to protect areas that have not been invaded yet.”

What would Enloe do about my gecko?

“Anything with a face becomes more difficult to deal with,” he conceded. “So you have to think of the number of other faces that [invasives] kill.” Enloe called his thought process ecological triage. “It’s an awful thing, but if there are invasive species causing major damage, triage that gecko,” he told me.

I still didn’t like the idea of being an executioner. After all, species appear, evolve and disappear all the time in the natural world. Change is an evolutionary constant. Wouldn’t nature manage to find a balance, with Florida eventually adapting to golden-eyed Gloria and her fellow alien intruders?

Ray Vinson, a land manager with Manatee County's Parks & Natural Resources department, seemed like the right person to ask. When I called him and said I wondered whether we should just let Florida’s ecosystems sort themselves out, he told me he wanted to show me what managed land looks like in comparison to land that has been left alone or developed without an understanding of natural ecosystems.

I drove to a spot east of I-75, near Lake Manatee, to meet him. We walked along a dirt path bordered by a barbed wire fence. On our right was the land-managed Rye Preserve. On the left was Faulkner Ranch. The preserve was an open space with few trees and lots of brush. The ranch was crowded with pine trees.

To the untrained eye, the area with more trees looked healthier. But Vinson explained that it’s not healthy for pines to be so close to each other. In nature, wildfires would thin them out, he said, but when they crowd together, the trees displace habitat for animals like the endangered Florida scrub jay.

“We offer to remove invasive plants and remove pines, but most ranchers aren’t that interested,” Vinson said.

Then he pointed out the cogongrass.

This plant—considered a weed, but then, weeds are really just plants we don’t like—was brought from Asia to Alabama to be used as cattle feed.

“They didn’t realize that the grass has all these barbs, and the cows won’t eat it,” Vinson said. The plant was abandoned as feed, but not before it colonized rural Florida. Then some Florida ranchers thought they’d try it as feed themselves, expecting different results, and now here we are.

“The urban boundaries are even worse,” Vinson said.

We drove across a state road from the preserve to another managed area. This one was next to a newly developed gated community called River Wind. As we walked through the development, Vinson stopped every couple of minutes to point out a different non-native species, including the highly toxic rosary pea and the deep-rooting guinea grass. It will be nearly impossible to get rid of all of them. He lamented losing the native species to invaders. “We are losing potential life-saving pharmaceuticals when native plants go extinct,” he said.

Apparently, I realized, nature needs help in finding a healthy balance. I asked Vinson what he would do with Gloria.

“I’d see if someone wants it as a pet,” he said. “If it were a Cuban tree frog [an intruder that’s causing many problems in Florida, including in suburban neighborhoods], I’d happily humanely euthanize it.”

The green iguana thrives in Southwest Florida backyards.

Image: Jason Heid/Shutterstock.com

One invasive species Floridians don’t seem to have any trouble euthanizing is the green iguana. An entire cottage industry of pest removal companies has cropped up to eradicate them. They’ve been spotted in Phillippi Creek in Sarasota—creating lots of arguments on Nextdoor about whether to kill them—and as far north as Gainesville. But they are firmly established farther south, especially in Naples and Miami, where the deft swimmers navigate networks of manmade canals to colonize residential back yards. That iguanas seem to prefer to settle in human-disturbed areas rather than the wild might make you wonder what kind of “nature” is being restored when we kill them.

I asked Jeremiah Doody, a professor at the Department of Integrative Biology at USF, whether the companies exterminating iguanas are helping to solve the state’s crisis of invasive species.

“The occasional killing of a few iguanas doesn’t really amount to much,” he said. “I have to teach my undergrads over and over that killing the odd animal is not helping.”

He’s had students run over exotic frogs in the belief that they are making a difference. “But the fact of the matter is you’re not doing any good,” he said. “You’re probably just being cruel.” Besides, Doody said, iguanas aren’t causing a lot of damage to the environment. They’re more a nuisance to human endeavors. They eat the flowers in people’s gardens and burrow into the ground, ruining sidewalks and seawalls.

But leaving invasive animals alone is not what the public wants to hear, Doody admitted. “Today, conservation trumps animal welfare, but there’s no clear answer,” he said. “We need impact studies. They’re cheap and we could figure out the impact of each invasive species in Florida and rank them accordingly.” From these studies, we could then determine which animals are truly harmful and which we can just leave alone.

As for my gecko?

Although he doesn’t believe I should let it back into the wild, “I wouldn’t kill that animal,” Doody said. All the geckos we see around houses and buildings are invasive, he pointed out. “The native geckos don’t hang around houses. And if the tokay is going to eat other geckos, they’re going to be eating invasive ones, so ultimately they’ll contribute to removal just as well.”

Gloria was still in the cardboard box, living off the grubs and palmetto bugs I tossed to her. Everything I’d read about tokay geckos warned they weren’t for amateur keepers. Gloria had shown nothing but hostility and loathing towards me, biting my fingers every time they got too close. I harbored no fantasies about our forming an interspecies bond, but neither killing her nor releasing her into the Florida environment felt right. I hoped I had found someone who might understand my dilemma when I discovered anthropologist and author Eben Kirksey, a New College graduate who teaches at Australia’s Deaken University. He is described as an “expert on science and justice” and studies the intersection of humans and animals.

In his book Emergent Ecologies, Kirksey had posed exactly the question that was consuming me: “When should we let unruly forms of life run wild and when should we intervene?”

No fan of what he calls the “abstract ideal of the native,” Kirksey said it’s impossible to recreate a natural Eden that never really existed, anyway. Instead, we dwell in a world of complex, constantly evolving ecosystems, where man is the most destructive invasive species of all. Not even the deepest parts of the ocean are left untouched by human development, and scientists warn that within the next few decades, our actions will annihilate more than 1 million more plants and animals. Yet we consider the entire earth our own and are the arbiters of what gets to stay and what must leave.

We don’t always understand the actual effects of an invasive species, Kirksey warned. He pointed to his work with the rhesus macaques in Florida’s Silver Springs. He concluded that the monkey, in spite of the media hysteria surrounding its herpes (the only documented case of the virus infecting a human was in a lab), is not ecologically harmful and has earned the right to call Florida home. “I see a lot of displaced anxiety about human impact in the world being put onto other animals,” he said.

Successfully dealing with invasive species, Kirksey contends, requires better political and economic choices, from limiting pollution to developing with more environmental awareness. “Rather than looking at managing life and death in these spaces that have been set aside as preserves or wild places or forested areas, why aren’t we thinking about regulating human enterprises more?” he asked.

I was beginning to feel overwhelmed by the magnitude—and maybe the hopelessness—of the issues Kirksey was raising. In the face of so much human folly and environmental destruction, what difference did the life of one little gecko make?

But then he said something that spoke straight to my heart.

“In this era of extinction,” he declared, “we can each ask a very personal question: ‘Who do we love?’” Whether the answer is geckos or monkeys or birds or snails, he said, the kind of life we value inspires us to exercise our curiosity, to investigate and learn more about it and the environment we share.

All the ways the world needs saving can feel out of reach. I’ve never even seen an iceberg. But somehow, this gecko from all the way across the planet ended up in my back yard and presented me with a choice.

After all I’d learned, I couldn’t square the circle that the solution to life is death. So I chose life for Gloria. She and I felt contained in our own little world, and I decided I would protect her from the world and protect the world from her.

I got a 50-gallon terrarium and heat lamp, filled the bottom with gravel and branches, and went to transfer Gloria into her new home. I opened her cardboard home and out she jumped. I lunged for her, but it was too late. She found a hole in the porch screen, slipped away and disappeared. In spite of all my agonized consideration, she had made her own plans for her life.

Isaac Eger is a Florida native whose stories have appeared in The New York Times, L.A. Times, Medium, Sports Illustrated, Men’s Health, Deadspin, and in the book The Wilder Heart of Florida. His latest Sarasota Magazine feature, about the privatization of Florida’s beaches, was “A Line in the Sand.”